N.H. Holocaust survivor tells story, discusses how it resonates today

| Published: 04-23-2017 11:57 PM |

Not much can stop Kati Preston from telling her story.

The 78-year-old Holocaust survivor had a knee replacement operation almost three weeks ago. Recovery requires lots of bed rest in her Barnstead farmhouse, and most would probably prefer to take it easy while they heal.

But Preston said there’s an urgency to her message that didn’t exist when she started speaking publicly about her life 10 years ago. Back then, her story was “Like a memory ... like a story, more historical than anything,” she said. Now, there’s a change, she said, in the America she journeyed to 38 years ago, the country she loves – an attitude that suggests it’s okay to engage in hate speech and to use a group of people as scapegoats for the country’s problems.

It’s a mission, she said, that has meant more to her than any other profession she’s ever held. More than being a journalist, an EMT or founding the a nonprofit theater organization.

It’s that urgency, she said, that had her speaking to an army medical unit in Portsmouth just nine days after her surgery. She had to sit in a wheelchair to tell her story then, but she hopes she’ll be able to stand Monday when she gives a talk at 7 p.m. at Rivier University’s Dion Center in Nashua in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Her energy, she said, is better when she stands.

Besides the change she feels in the country, she said she fears she’s running out of time to tell her story. An estimated 100,000 Holocaust survivors are still alive today in the U.S., according to the Conference of Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, and by 2020, that number is expected to drop to 67,100. By 2030, the number of survivors is expected to drop to a mere 15,800.

An estimated 6 million Jewish people died in the Holocaust, a figure that does not encompass the Romas, the Polish or Serb civilians, among others, who were killed by the Nazi regime, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

It’s a lonely existence, Preston said, and as survivors die she fears the memory of the Holocaust will eventually be lost, unless people hear their stories. So she speaks, because she can’t afford not to. Now, more than ever, she said, people need to understand the dangers of allowing hatred of others to rule their actions, and the dangers of being complicit in that hatred.

Just ask her about what happened to her father.

Before the Hungarian authorities rounded up all the Jewish inhabitants of Nagyvarad, a village in what is now considered Romania, Preston lived a secure life. Her mother, a fierce, bright Catholic woman, employed 40 women in a successful dressmaking business; her father, a tall, dark Jewish man with a big laugh, supplied the whole region with carp from the Koros river with his wholesale fishing businesses. Their interfaith marriage, Preston said, was a bit of a scandal at the time.

Preston was treated “like a princess,” she said, especially by her father, who always had a gift for her in his pocket when he came home. He made her feel safe, she said, even when he threw her in the air and caught her. When he held her, she felt a sense of love, peace and security – one, she said with a pause, “I’ve never recaptured.”

When authorities required all the Jewish residents to register at the police station around 1943, Preston was too young to perceive the threat. At age 4, she couldn’t understand that registration turned into denying Jewish people the ability to go to college, or that Jewish doctors weren’t allowed to treat non-Jewish patients, or that she wasn’t even allowed to sit on her favorite bench anymore because she was Jewish.

Even when her mother presented her with a golden Star of David, which she wore proudly until a man spat on her in the street, Preston wasn’t worried – the concept of hatred, or death, was foreign to her as a child.

So when her father disappeared behind the walls of a ghetto, Preston wasn’t afraid.

“He was my daddy,” she said. “He wouldn’t leave me.”

Preston wouldn’t find out what happened to her father until after the war was over. She learned her mother had bribed some authorities to release her father, and he almost escaped; the night he was recaptured, he was supposed to walk across the Romanian border.

But he couldn’t leave, Preston said, without saying goodbye to his daughter. He set out for the outskirts of a nearby village, where Preston hid for three months after a peasant woman named Erzsebet who delivered milk to her family spirited her away to avoid going into the ghetto.

He was captured, she learned, and deported the next day to Auschwitz.

In Auschwitz, Preston’s father was caught trying to steal a piece of bread, a transgression he was beaten for and, ultimately, paid for with his life. But Preston wouldn’t learn of this until much later, when her stepfather, a man named Erno, told her on his deathbed. Erno had also lost loved ones – his wife and child, an 11-year-old named Ditta – to Auschwitz’s gas chambers.

Preston said she knows that could have been her were it not for Erzsebet. She hid Preston in her barn attic among the hay and big, black spiders. She was there, watching through the cracks in the walls, when three men in green uniforms appeared at the farmhouse. They had been tipped off by one Preston’s mother’s workers, who knew she had a child.

Preston watches as the men slapped Erzebet around. “Where’s the Jew?” they demand.

“Search my house,” she replied.

They searched with gusto, throwing furniture out the window. As the soldiers were about to leave, one got the idea to check the barn. The sounds of what happened next stand out strongest to Preston: The clomp of the soldier’s black, heavy boots, making their way up the barn’s rickety steps; the beating of her heart, so loud she was certain the soldiers would hear it; the twang of metal sticking into wood just inches from her face as a soldier poked the hay with a bayonet.

Preston said that was the moment she understood death. As an adult, when she heard of how her father died, she understood another emotion: hatred.

“It was almost like a psychosis. I wanted revenge – I was filled with these incredible fantasies about what I would do to the people who killed my father,” she said. “My soul was so full of hatred there was no room for anything else.”

That hatred, she said, took 50 years to leave her.

One of the most common questions Preston gets when she speaks is, “What do you do for revenge?”

More than 73 years after the Holocaust, a corner of Preston’s Center Barnstead farmhouse is filled with pictures of her family. Her mother, who married Erno and eventually moved to America with Preston and her husband, Gordon, is gone, as is Erno, but her four children and their children remain.

Their family is multicultural, Preston said – the four grandchildren are half-Chinese, half-Mexican, half-African American, and half-German. The half-German child is the granddaughter of a German soldier, and Preston said when she first learned her son was marrying the descendant of a Nazi, she gulped, then gulped again, collecting herself.

“I said, ‘That’s okay; we don’t revisit the sins of the father on the children,’ ” she said.

The birth of her half-German granddaughter closed the circle for Preston; now, she said, her heart is “full of love,” and she hopes her message can stem the rising tide of intolerance and scapegoating of minorities she sees going on in the U.S. today.

Despite that, she disagrees with the notion that America is in danger of following in Germany’s footsteps.

“When Hitler took over, Germany was on its knees,” she said. “People say America is, but it’s not, and that’s a big difference.”

Preston also has a lot of hope for the younger generations that she views as being more tolerant. She gains strength from the reactions of the children she speaks to at schools, from their desire to touch her and take selfies with her.

But the older generations can’t slack off either.

“It’s very scary,” she said. “It’s going to take another generation to get away from this. I tell my kids, ‘You’re going to be here for a long time. What you do today is going to affect your kids, and your kids’ kids.”

She urges people to remember what can happen when intolerance wins. She doesn’t want people to forget her, or Ditta, whose fate could have easily been hers, if not for Erzebet. She wants people to remember that without her, Preston’s children and grandchildren would not exist.

Preston often looks at a picture of her and her father. She’s sitting on his shoulders at a pool, giving him rabbit ears. It’s the last picture ever taken of the two of them together.

“What do I do for revenge?” she says. “I live.”

(Caitlin Andrews can be reached at 369-3309, candrews@cmonitor.com or on Twitter at @ActualCAndrews.)

]]>

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

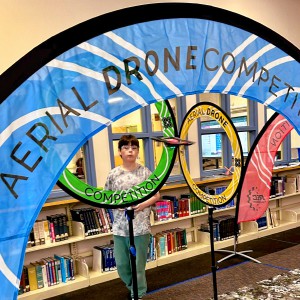

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda