Missing for more than a century, Revolutionary War-era printing plate returns to N.H.

| Published: 10-09-2018 8:43 AM |

Nearly a decade after the state unsuccessfully pursued a collector in Minnesota to retrieve a New Hampshire artifact, the item has returned to the Granite State.

With the financial support of private donors, the New Hampshire Historical Society purchased at auction a rare copper printing plate used to print currency that underwrote the state’s share in the Revolutionary War effort.

The plate was engraved by Exeter metalsmith John Ward Gilman on June 9, 1775, as the colonies were on the cusp of the war for independence from the British empire.

A copper sheet about the size of a legal pad and weighing roughly 2¾ pounds, the artifact is humble in appearance but represents a fervent period of patriotism, said Bill Dunlap, president of the N.H. Historical Society.

“It’s a piece of metal, but it tells a story,” he said. “That’s the power of these artifacts is you begin thinking about the era in which the people lived to produce this and the risk they were taking – they’re printing up this new currency to pay for a rebellion against the king of England. It fires up your imagination.”

It also fired up a legal dispute in 2010 when a man who obtained the piece at an estate sale in Spring Valley, Minn., tried to sell it at a national auction in Boston.

The collector, Gary Lea, received a letter from the New Hampshire Attorney General’s office on the morning of the sale demanding that he remove the artifact from the auction or risk facing legal action, according to Monitor reports at the time.

Lea and the attorney general’s office, then under the direction of Michael Delaney, engaged in a legal scuffle disputing rightful ownership of the copper plate. That saga ultimately reached a stalemate while the copper plate remained locked away in safety deposit box in Minnesota.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Former Franklin High assistant principal Bill Athanas is making a gift to his former school

Former Franklin High assistant principal Bill Athanas is making a gift to his former school

Another Chipotle coming to Concord

Another Chipotle coming to Concord

Generally speaking, Don Bolduc, now a Pittsfield police officer, has tested himself for years

Generally speaking, Don Bolduc, now a Pittsfield police officer, has tested himself for years

Lea made an offer to sell it back to the state, but at a price that Dunlap described as “sort of out of the realm of feasibility for anybody.”

“Everybody sort of went back to their respective corners, took a breath, and here we are seven years later,” he said. “There was a more feasible price, but still significant. We bid on it and got it. Sometimes patience is rewarded.”

The item sold on Heritage Auctions for $18,000, according to the auction’s website.

The N.H. Historical Society is now working to fill in the blanks in the history of this copper printing plate. Gilman, who also designed the state’s seal in 1776, died in Exeter in 1823 at the age of 82.

The state lost track of the plate for at least 150 years from 1850 through the early 2000s before Lea inadvertently discovered it in 2009.

The society speculates that in the 1850s, a New Hampshire government official borrowed the plate from a state house vault to lend to a collector in Baltimore who wanted to print commemorative copies of the currency, but the plate was never returned.

“It’s great to have it here, fabulous to have it in the state of New Hampshire,” Dunlap said.

Wesley Balla, director of collections and exhibitions for the New Hampshire Historical Society, says the piece will eventually be put on display for public viewing.

Until then, Balla said a conservator will examine the plate and recommend treatment, if necessary, to ensure its preservation. Copper and other metals will oxidize on their own, Balla said, so the plate will be stored in a container to minimize air contact.

“The goal for this institution and others is to really get objects, materials, into publicly accessible hands and preserve them so they don’t go back under cover and are not seen for another 100 years,” he said.

(Nick Stoico can be reached at 369-3321 or nstoico@cmonitor.com.)

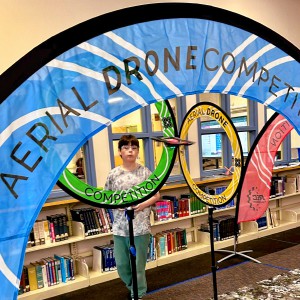

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure

Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure