‘We’re just kids’: As lawmakers debate transgender athlete ban, some youth fear a future on the sidelines

Maëlle Jacques plays soccer and runs track at Kearsarge Regional High School. If Senate Bill 375 is signed into law, Jacques, a transgender girl, will no longer be allowed to play on the girls' sports teams. —Courtesy

|

Published: 04-19-2024 2:05 PM

Modified: 04-19-2024 2:38 PM |

Maëlle Jacques has read the articles written about her.

“Winner of NH Girls High Jump is Biological Male.”

“Transgender girl blasted after dominating New Hampshire girls high jump.”

“U.S. ‘Full of Failing Gutless Mothers and Fathers’: High School Boy Defeats Girls in High Jump Competition.”

Jacques, a 16-year-old sophomore at Kearsarge Regional High School, runs track and plays soccer, but her ability to continue to participate in the two sports she loves is in peril. On April 5, the New Hampshire Senate voted to pass SB 375, a bill that would ban Jacques and anyone else assigned male at birth from playing on girls’ or women’s sports teams. All 14 Senate Republicans voted in favor of the ban; all 10 Democrats voted against it. The House Education Committee will hold a public hearing on the bill Monday.

Jacques began transitioning when she was 11 years old. She’s seen her family slandered, her school district threatened and her coach verbally attacked. She’s had no reason to read all the hate and vitriol directed at her. But she’s determined to try to understand their point of view.

“I’ve read enough of the articles to somewhat understand where some of the hate comes from,” she said. “I can understand profes sion ally, regulations in sports, and I can comprehend the perspective. But oftentimes, they do n’t take the consideration to do the same and understand my perspective.”

There’s one big question Jacques has for New Hampshire politicians in favor of a complete ban: Why not a compromise?

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

Kenyon: What makes Dartmouth different?

One injured in downtown Franklin shooting, police investigating

One injured in downtown Franklin shooting, police investigating

NH Center for Justice and Equity releases policy goals to address racial disparities

NH Center for Justice and Equity releases policy goals to address racial disparities

NHTI to treat Medicaid dental patients after $500,000 donation

NHTI to treat Medicaid dental patients after $500,000 donation

Opinion: A veteran, father, and coach’s plea to reject homophobic laws

Opinion: A veteran, father, and coach’s plea to reject homophobic laws

Concord High graduate leads Pro-Palestine protests at Brown Univeristy

Concord High graduate leads Pro-Palestine protests at Brown Univeristy

The NCAA’s policy stipulates that transgender women athletes can participate in collegiate competition so long as they’ve been undergoing testosterone suppression treatment for at least a year and that they present documentation that shows their hormone levels meet the required thresholds for each sport. As such, there’s a clear path for the athletes to participate.

“As much as I realize for myself and a lot of the community it’s not the greatest scenario, it’s better than an outright ban in my eyes,” Jacques said. “I wish people would understand that we’re just kids who want to play and have fun and be in a community. It’s not a malicious thing that we’re doing.”

The N.H. House would still need to pass the bill and Gov. Chris Sununu would need to sign it to become law. Sununu’s stance is unclear. In 2018, he signed a bill that banned discrimination based on one’s gender identity and another bill that banned conversion therapy for minors, moves that drew the ire of some fellow Republicans.

“If we really want to be the ‘Live Free or Die’ state, we must ensure that New Hampshire is a place where every person, regardless of their background, has an equal and full opportunity to pursue their dreams and to make a better life for themselves and their families,” he said at the time.

Last spring, when the U.S. Department of Education proposed a rule that banning transgender athletes from participating in sports would be in violation of Title IX, Sununu argued this wasn’t an issue for the federal government to take a stand on.

“The best solutions are at the local level, ultimately up to each school and league — not a one-size-fits-all approach out of Washington,” he said.

Sununu’s office did not respond to a request for comment on SB 375.

Still, this issue has become a priority among Republican politicians and organizations who have vowed to protect and stand up for women’s sports.

“A strong trans girl is going to prevent a biological female from winning titles and being recognized in their accomplishments,” State Senator William Gannon, a Sandown Republican, said before a vote on SB 375 on April 5. “And it’s not really the best athletes, the best women athletes I’m concerned with. It’s really going to hurt the girl, the 11th girl who doesn’t make the team on a 10-woman roster. They’re the ones who aren’t going to learn these leadership roles. They’re not going to mix, so we are hurting biological females here, and I don’t want to put them or the other girls in New Hampshire at that disadvantage.”

Currently, 24 states have passed laws that ban transgender students from playing sports according to their gender identity. It’s an issue that’s talked about like it’s widespread. Statistically, it’s quite rare.

Out of the roughly 200,000 women who compete in NCAA sports, it’s estimated that 50 of them are transgender. In other words, the number of transgender women competing at the NCAA level couldn’t even fill one row at Michigan Stadium, the college football venue that holds over 100,000 people.

Roughly 1.6% of Americans identify as transgender. In high school athletics, it’s estimated that less than 0.5% of student-athletes are transgender. The New Hampshire bill seeks to address an issue that is highly infrequent. No solid estimates exist for the number of transgender athletes in the Granite State.

This February, Jacques placed first in the high jump at the New Hampshire Interscholastic Athletic Association’s Division II indoor track championships. Her winning jump of 5’2 was the same as the competitor who placed second (based on tiebreakers). The third-place finisher recorded a jump of 5’0 and fourth, fifth and sixth place all finished with jumps of 4’10. That’s compared to the boys’ high jump that saw five jumpers reach 6’0.

If she had competed in the Division I competition, she wouldn’t have placed first (Concord’s Ella Goulas reached 5’4). And if she competed in Massachusetts, she wouldn’t have won in four of the state’s five divisions — all of which saw the winning girls deliver jumps of 5’4.

Jake Maxwell’s family already has plans to move out of New Hampshire to California in hopes of finding a place more welcoming to his transgender daughter who’s 11. The rush of legislation against the rights of transgender children, he said, has simply become too much to justify continuing to call the Live Free or Die state home.

Like Jacques, Maxwell expressed an understanding for why people would want to have this conversation about collegiate and professional athletes when there’s more at stake. But this bill in New Hampshire, he said, is far too extreme because it would ban participation.

“It’s a child’s life, and kids are committing suicide,” Maxwell said. “It’s just basically legalized bullying.”

According to data collected by The Trevor Project, an organization devoted to suicide prevention for LGBTQ youth, nearly 60% of transgender youth surveyed had considered suicide in the previous year and nearly a quarter had attempted suicide.

“These bills aren’t to protect children, they’re not to protect free speech; they’re to tell a person that they don’t belong and that they should not exist and that it’s harder if they exist,” Maxwell said. “That is the inner workings of these things, and that’s why we’re leaving. If it’s sports or whatever it is, if you are telling a kid that it’s harder for everybody else if they exist, that’s how kids commit suicide.”

Maxwell’s daughter loves to ski. She won’t be able to ski much in California, but her father said the big-picture tradeoff will be worth it.

“The fact that you’re taking something away from a kid and telling them that they can’t exist is far more damaging than anything that could ever come out of an 11-year-old going down a hill. It’s such a farce that people are saying this is about protecting children because it’s directly harming children,” Maxwell said. “Skiing is just a place for her to be free and a place for her to be who she is and be a kid.”

Jacques conveyed a similar feeling, in how sports have allowed her to feel like she’s part of something. After spending so much of her life questioning who she was and how she lives her life, sports bring her a kind of catharsis.

“A lot of times as a trans kid, you can feel like an outcast; in many social groups, you aren’t accepted,” Jacques said. “In terms of a soccer team, team sports, people look past that and less of who you are as a person and how you can help on the team.”

For Jacques, it’s far more than about the wins and losses; it’s about being part of a community.

“It helps my mental health — especially if I’m having bad thoughts or something. If I’m running, I’m not thinking about those because I’m focusing on trying to do my best, just being with my friends,” she said. “It’s been huge for me socially, kept me from being sad.”

Research from the National Institutes of Health finds no noticeable athletic advantage for someone who transitions before puberty or for people who begin gender-affirming care at the start of puberty.

“There is no reason for transgender children who are prepubertal to do anything other than to participate in sport in the sex category that makes sense for them socially,” the report says.

“It is possible that larger physical stature may be an advantage for some sports,” the report adds. “It is also possible that a person with larger stature from a typical male puberty but with smaller muscle mass due to a testosterone-lowering regimen might suffer an athletic disadvantage.”

This is why NCAA guidelines are broken down based on sport while continuing to align with available research to allow a path for transgender women to participate and compete.

Senator Rebecca Perkins Kwoka, a Portsmouth Democrat, introduced an amendment to SB 375 aligned with this philosophy that outlined a pathway for participation while also acknowledging concerns about possible competitive advantages.

“It prohibits some of our kids, indeed some of our most vulnerable kids, from participating in a basic form of child interaction: play,” she said on April 5. “The stated claim of the sponsors of SB 375 is to promote fairness in sports. This amendment addresses that issue directly, instead of attacking the identity of our children. The New Hampshire Interscholastic Athletic Association and the NCAA guidelines already establish standards for eligibility. This amendment ensures that the NHIAA and individual schools are able to set requirements that ensure fairness without running afoul of the law against discrimination in schools.”

The proposed amendment failed on a party-line vote, with the 10 Democrats supporting it and the 14 Republicans opposed.

If this bill is passed by the N.H. House and signed by Sununu, Jacques said she won’t play any sports for her high school. She’s run into some of her biggest challenges, she said, from male athletes in the past. She’s never thought it to be a welcoming environment for her.

She plans to continue to fight, though, meeting with politicians and organizations to help reverse a potential ban at some point in the future.

“I still want it to be fair for the others in my position,” she said. “I want them to have the chance to enjoy sports like I do because they mean the world to me. I can go into a little separate world and not worry about all the craziness going on elsewhere.”

Still, she conveyed a sense of helplessness about an outright ban that feels directed at her.

“It’s really disheartening to me because I feel like as a country since I’ve been born, we’ve made so much progress in LGBTQ rights, and to see that position be (reversed), it’s a hard thing to see,” Jacques said. “I find the direct ban without any consideration to be quite extreme and hard to deal with because I feel like I can’t do that much because there are no negotiation grounds.”

Update: Reactions for, against the more than 100 arrested at Dartmouth, UNH

Update: Reactions for, against the more than 100 arrested at Dartmouth, UNH Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

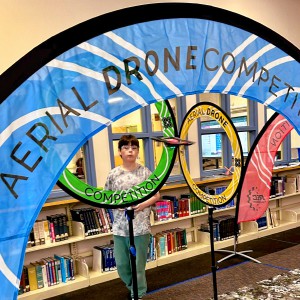

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition