Latest News

Obiri, Lemma claim Boston Marathon

Obiri, Lemma claim Boston Marathon

Dinner over death in Concord

Dinner over death in Concord

Another Chipotle coming to Concord

Another Chipotle coming to Concord

Portsmouth temple again targeted with vandalism

Portsmouth temple again targeted with vandalism

Vandals key cars outside NHGOP event at Concord High; attendee carrying gun draws heat from school board

Vandals keyed the cars of at least 10 members of the state Republican Party while the group held its biennial convention inside Concord High School on Saturday. “There’s already too much vitriol in partisan politics,” Party Chair Chris Ager said. Ager...

Former Franklin High assistant principal Bill Athanas is making a gift to his former school

Bill Athanas saw the sign outside Laconia High School and flashed back to the hallways of Franklin High.He remembered walking past the plain Franklin High sign – white letters on a black background, flanked by two small brick pillars – and greeting...

Most Read

Editors Picks

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Sports

High schools: Concord boys’ lax earns first win, plus more weekend results

Boys’ Lacrosse Concord 9, Dover 8 Key players: Concord – Carter Doherty (5 goals), Jaden Haas (4 goals), Brayden Beauregard (3 assists), Tyler Morin (assist), Ben Ryder (assist), Logan Shimer (goalie), Noah Wyatt (defense), Broc Pelchat (defense),...

High schools: Wednesday and Thursday’s results

High schools: Wednesday and Thursday’s results

Bow girls’ lacrosse coach Chris Raabe achieves milestone win

Bow girls’ lacrosse coach Chris Raabe achieves milestone win

High schools: Bow girls’ lax coach Raabe wins 300th game, more Wednesday results

High schools: Bow girls’ lax coach Raabe wins 300th game, more Wednesday results

Boys’ lacrosse: Hopkinton and Bow head to overtime in season opener

Boys’ lacrosse: Hopkinton and Bow head to overtime in season opener

Opinion

Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation

Bob Sanders lives in Concord. On a rainy April 10, I with the help of one other delivered a message on behalf of 67 New Hampshire Jews to the office of Rep. Annie Kuster in Concord, calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, humanitarian aid, and cutting off...

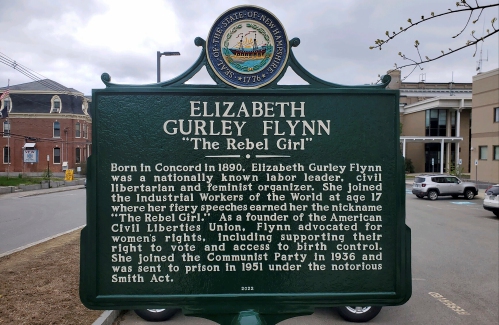

Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history

Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history

Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down

Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down

Opinion: New Hampshire, it’s time to drive into the future

Opinion: New Hampshire, it’s time to drive into the future

Opinion: Eid al-Fitr in Gaza: A war against humanity itself

Opinion: Eid al-Fitr in Gaza: A war against humanity itself

Politics

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

The House narrowly approved a bill Thursday that would eliminate any exceptions to the state’s voter ID laws and require documentary proof of citizenship to vote, 189-185. The bill, House Bill 1569, would require a person registering to vote to...

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

As NH lawmakers eye statewide housing solutions, local control remains a barrier

As NH lawmakers eye statewide housing solutions, local control remains a barrier

On the trail: Haley was first in and last out

On the trail: Haley was first in and last out

Haley will suspend her campaign and leave GOP to Trump

Haley will suspend her campaign and leave GOP to Trump

Arts & Life

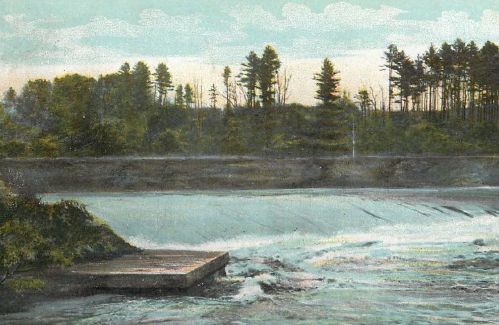

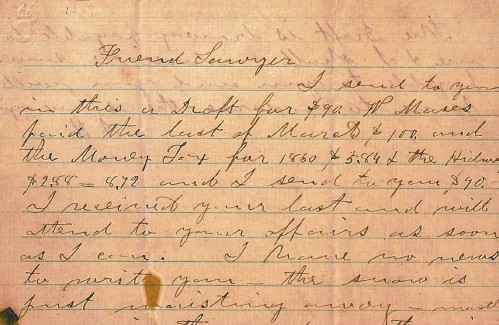

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

It was almost two hundred years ago when our Concord ancestors thought and planned and then they planned and thought again. They dreamed about what could be and about the riches that might follow. A period of time commonly referred to as the Second...

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

From the archives: Civil War brewing

From the archives: Civil War brewing

From the farm: Celebrate springtime

From the farm: Celebrate springtime

National Water Dances comes to NH

National Water Dances comes to NH

Obituaries

Candice Myatt

Candice Myatt

Rochester, NH - Candice E Myatt, 74 of Rochester NH, formerly of Barnstead NH passed away unexpectedly on Wednesday evening at her home. She grew up in Weare NH with her father Carl Hoyt Sr... remainder of obit for Candice Myatt

Darla Jean Welcome

Darla Jean Welcome

Penacook, NH - Darla Jean Welcome died very unexpectantly on Friday April 7, 2024. Darla was predeceased by her husband Dean Welcome and father David Randlett Jr. She is survived by her mot... remainder of obit for Darla Jean Welcome

Paul J. St. Germain

Paul J. St. Germain

Allenstown, NH - Paul St. Germain, 83, of Allenstown NH, passed away on April 11, 2024. He was born in Hooksett NH to the late Damase and Georgianna (Morgan) St. Germain. Paul had worke... remainder of obit for Paul J. St. Germain

Winnifred H. Bailey

Winnifred H. Bailey

Boscawen, NH - Winnifred H. Bailey, age 81, passed away peacefully on Tuesday, April 9, 2024 at Merrimack County Nursing Home. She was born in Concord, NH the daughter of the late Cecil an... remainder of obit for Winnifred H. Bailey

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

High schools: Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

High schools: Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure

Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure

NH resident pleads guilty to selling stolen body parts

NH resident pleads guilty to selling stolen body parts