Latest News

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

After Thursday’s 7:30 p.m. showing of “Kung Fu Panda 4,” the Regal Cinema on Loudon Road will close for good, ending 28 years of multiplex movies on The Heights in Concord and marking the latest step in the redevelopment of the Steeplegate Mall.What’s...

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

At the start of the year, Concord Casino was ordered to close its doors and sell the business within six months, but, so far, no buyers have stepped forward to acquire the establishment.“There’s been no change in the status of the Concord facility,”...

Most Read

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

Former Franklin High assistant principal Bill Athanas is making a gift to his former school

Former Franklin High assistant principal Bill Athanas is making a gift to his former school

Another Chipotle coming to Concord

Another Chipotle coming to Concord

Vandals key cars outside NHGOP event at Concord High; attendee carrying gun draws heat from school board

Vandals key cars outside NHGOP event at Concord High; attendee carrying gun draws heat from school board

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

On the Trail: New congressional candidate spotlights border, inflation, overseas conflicts

On the Trail: New congressional candidate spotlights border, inflation, overseas conflicts

Editors Picks

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Sports

High schools: Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

BaseballMerrimack Valley 4, Bow 3Key players: MV – Luke Dougherty (win, 5 IP 8 K), Will McPherson (save, 2 IP, 0 H), Jonas Weed (2-for-4, 2 RBI), Seth Norris (double); Bow –Jake Reardon (2-for-3, double, RBI), Owen Webber (1-for-3, RBI, run), Colby...

Obiri, Lemma claim Boston Marathon

Obiri, Lemma claim Boston Marathon

High schools: Concord boys’ lax earns first win, plus more weekend results

High schools: Concord boys’ lax earns first win, plus more weekend results

High schools: Wednesday and Thursday’s results

High schools: Wednesday and Thursday’s results

Bow girls’ lacrosse coach Chris Raabe achieves milestone win

Bow girls’ lacrosse coach Chris Raabe achieves milestone win

Opinion

Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation

Bob Sanders lives in Concord. On a rainy April 10, I with the help of one other delivered a message on behalf of 67 New Hampshire Jews to the office of Rep. Annie Kuster in Concord, calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, humanitarian aid, and cutting off...

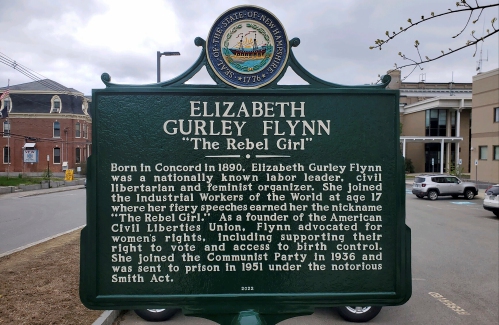

Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history

Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history

Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down

Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down

Opinion: New Hampshire, it’s time to drive into the future

Opinion: New Hampshire, it’s time to drive into the future

Opinion: Eid al-Fitr in Gaza: A war against humanity itself

Opinion: Eid al-Fitr in Gaza: A war against humanity itself

Politics

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Angela Brennan of Bow and Rebecca McWilliams of Concord, both Democratic State Representatives, have entered the race for the New Hampshire State Senate in District 15, to fill the shoes of Sen. Becky Whitley, who is eyeing a congressional seat.The...

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

As NH lawmakers eye statewide housing solutions, local control remains a barrier

As NH lawmakers eye statewide housing solutions, local control remains a barrier

On the trail: Haley was first in and last out

On the trail: Haley was first in and last out

Arts & Life

Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April

SKIT, the Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater, presents Olympus On My Mind, a funny, sometimes poignant, off Broadway musical featuring gods being naughty!Lessons are learned, delightful songs are sung, toes are tapped and this gem will leave you...

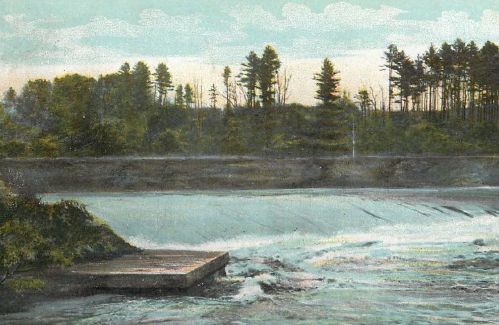

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

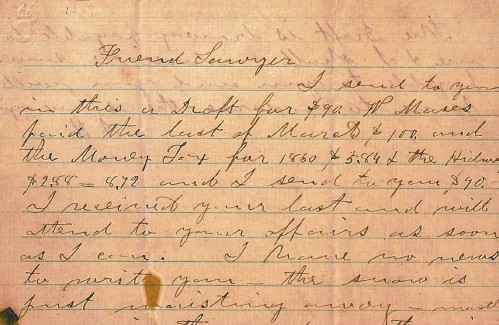

From the archives: Civil War brewing

From the archives: Civil War brewing

From the farm: Celebrate springtime

From the farm: Celebrate springtime

Obituaries

Jane A. Haskell

Jane A. Haskell

Boscawen , NH - Jane A. Haskell, 95, died peacefully on Saturday April 13, 2024, at Merrimack County Nursing Home. She was born in Dover, NH, the daughter of Amy (Towle) and Harold Brow... remainder of obit for Jane A. Haskell

Patricia L. Hews

Patricia L. Hews

Concord, NH - Patricia L. Hews passed away peacefully on April 3, 2024. "Pat," as she was known by most, was born on November 30, 1931 in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine. She is the daughter to Marga... remainder of obit for Patricia L. Hews

Candice Myatt

Candice Myatt

Rochester, NH - Candice E Myatt, 74 of Rochester NH, formerly of Barnstead NH passed away unexpectedly on Wednesday evening at her home. She grew up in Weare NH with her father Carl Hoyt Sr... remainder of obit for Candice Myatt

Darla Jean Welcome

Darla Jean Welcome

Penacook, NH - Darla Jean Welcome died very unexpectantly on Friday April 7, 2024. Darla was predeceased by her husband Dean Welcome and father David Randlett Jr. She is survived by her mot... remainder of obit for Darla Jean Welcome

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

High schools: Tuesday’s track, baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

High schools: Tuesday’s track, baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success

Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success

Concord city-schools committee revived, will meet for first time in 2 years

Concord city-schools committee revived, will meet for first time in 2 years

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

Opinion: Proposed height zoning change for Concord’s Main Street

Opinion: Proposed height zoning change for Concord’s Main Street

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams