Donna Daffy paints Dunbarton yellow with daffodils

Every spring morning, as the first rays of sunlight dance across Dunbarton, Donna Dunn is treated to a vibrant sea of yellow daffodils unfurling before her eyes.It’s a sight that fills her heart with indescribable joy, a gift that few are fortunate...

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

If you’ve attended a sporting event at Merrimack Valley High School, the odds are high you’re familiar with the voice of Nick Gelinas.Perched atop the press box during the spring and fall sports seasons and in the bleachers of the MVHS gym in the...

Most Read

Editors Picks

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

FAFSA fiasco hits New Hampshire college goers and universities hard

FAFSA fiasco hits New Hampshire college goers and universities hard

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Sports

Patriots’ draft approach likely to be different in post-Belichick era

FOXBOROUGH, Mass. — The 2024 NFL draft represents the next chapter in the remaking of the New England Patriots.Bill Belichick is gone after driving both the franchise’s on-field and personnel decisions for most of his more than two-decade run in New...

High schools: Weekend results

High schools: Weekend results

Opinion

Opinion: This Earth Day, help keep local land clean and healthy

Mike Cohen is the Principal Consultant for MJC HealthSolutions. Mike has served on many volunteer boards and committees in New Hampshire, contributing to efforts to improve the health and well-being of residents and protecting and preserving natural...

Opinion: Adopting the right 306 Rules

Opinion: Adopting the right 306 Rules

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Politics

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

As jury selection begins this week in the hush-money trial of former President Donald Trump, New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu says he doesn’t believe many voters view Trump’s criminal indictments, his actions on Jan. 6, 2021, or his election denialism...

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

Arts & Life

Active Aging: John Burke of Peterborough celebrated his 81st birthday with 81 hikes up Pack Monadnock

On March 29, John Burke of Peterborough marked his 82nd birthday.Now, he will have to come up with a way to top last year, when he challenged himself to celebrate his 81st birthday by hiking up Pack Monadnock in Peterborough every day for 81 days...

Vintage Views: From darkness to light

Vintage Views: From darkness to light

From the farm: Spring brings calves, beautiful calves

From the farm: Spring brings calves, beautiful calves

NH Furniture Masters present new member show this spring

NH Furniture Masters present new member show this spring

Obituaries

Dennis Michael Schwab

Dennis Michael Schwab

Manchester, NH - It is with great sorrow that we announce the passing of Dennis Michael Schwab. He passed away on April 6th, 2024, after a period of failing health. He was 51 years old. With great dignity, Michael was very thankful to b... remainder of obit for Dennis Michael Schwab

Jay T. Sweeney

Jay T. Sweeney

Lyman, ME - Jay T. Sweeney, 64, of Lyman Maine, Passed away unexpectedly on Tuesday, February 20, 2024. He was born in Concord, NH on October 13, 1959, son of John and Donna Cozzi, Sweeney. He graduated from Concord High school, Class ... remainder of obit for Jay T. Sweeney

Patrick J. Pat" Lane

Patrick J. Pat" Lane

Patrick J. "Packin' Pat" Lane Concord , NH - Patrick Joseph Lane of Concord NH passed away suddenly in his home on April 8th. He was born in Seattle Washington October 8,1959. The son of Leo T. Lane and Blanche (Renshaw) Lane, the third... remainder of obit for Patrick J. Pat" Lane

Lisa Marie Cheney

Lisa Marie Cheney

Lisa Marie (Jameson) Cheney Boscawen, NH - Lisa Marie (Jameson) Cheney, 56 of Boscawen NH, passed away peacefully April 17, 2024 at Granite VNA Hospice House with family by her side. Born in Concord, NH on April 20, 1967, Lisa was the da... remainder of obit for Lisa Marie Cheney

High schools: Bow’s Kelly lifts Falcon softball to victory in walk-off, more Monday results, plus Saturday’s track meets

High schools: Bow’s Kelly lifts Falcon softball to victory in walk-off, more Monday results, plus Saturday’s track meets

House committee weighs bill that would require teachers to answer parents’ questions

House committee weighs bill that would require teachers to answer parents’ questions

New Hampshire man convicted of killing daughter, 5, ordered to be at sentencing after skipping trial

New Hampshire man convicted of killing daughter, 5, ordered to be at sentencing after skipping trial

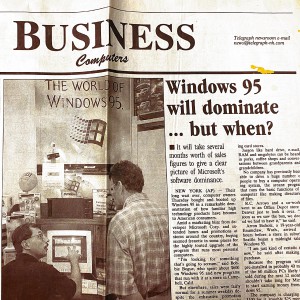

Granite Geek: 28 years after an ‘e-mail course’ a professor ponders changes to online courses

Granite Geek: 28 years after an ‘e-mail course’ a professor ponders changes to online courses

N.H. Educators voice overwhelming concerns over State Board of Education’s proposals on minimum standards for public schools

N.H. Educators voice overwhelming concerns over State Board of Education’s proposals on minimum standards for public schools

Diaper Spa owner faces mental health board

Diaper Spa owner faces mental health board

Emergency rooms at local hospitals are overcrowded. Here's what to know.

Emergency rooms at local hospitals are overcrowded. Here's what to know.

A trans teacher asked students about pronouns. Then the education commissioner found out.

A trans teacher asked students about pronouns. Then the education commissioner found out.

Republicans have made illegal immigration a top issue in NH – sometimes with misinformation

Republicans have made illegal immigration a top issue in NH – sometimes with misinformation

Gallery: Forty-mile gravel bicycle race draws racers from all over the region

Gallery: Forty-mile gravel bicycle race draws racers from all over the region Wednesday’s high schools: Fancher’s 2-run blast leads Concord baseball to victory; plus more baseball, softball, lax and tennis results

Wednesday’s high schools: Fancher’s 2-run blast leads Concord baseball to victory; plus more baseball, softball, lax and tennis results Softball: Maddy Wachter Ks 12, Concord holds off Winnacunnet in 2023 championship rematch

Softball: Maddy Wachter Ks 12, Concord holds off Winnacunnet in 2023 championship rematch Opinion: Student power: Confronting collaborators and cowards at home and abroad

Opinion: Student power: Confronting collaborators and cowards at home and abroad Opinion: Being and becoming: A good doctor in the age of artificial intelligence

Opinion: Being and becoming: A good doctor in the age of artificial intelligence Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April

Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April