Latest News

Hooksett’s new tower could improve coverage in Bow

Hooksett’s new tower could improve coverage in Bow

Rare bipartisan gun bill gets NH Senate hearing

Rare bipartisan gun bill gets NH Senate hearing

Pay-by-bag works for most communities, but not Hopkinton

Every time Jolene Cochrane clocks in for her shift at the Hopkinton Transfer Station, she sees residents driving in with their household waste bagged in various colored trash bags.With 19 years of experience at the station — a few years longer than...

Pembroke seminar on climate change aims to set the record straight

Ayn Whytemare doesn’t like the view from the top of her hayfield in Pembroke.From there, rising from pines like a lonely skyscraper, stands the smokestack used by the Bow coal plant, the last facility of its kind in New England. And while the visible...

Most Read

Editors Picks

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Sports

High schools: Tuesday’s track, baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

Boys’ TrackMerrimack Valley 110.33, Bow 101.66, Pembroke 44, St. Thomas 41, Bishop Brady 35Key players: MV – Nicolas Ogelsby (1st high jump, 1st long jump), Brayden Laroche (1st 100 hurdles, 1st 300 hurdles)), Mychal Reynolds (1st 400), Abhiman Karki...

High schools: Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

High schools: Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

Obiri, Lemma claim Boston Marathon

Obiri, Lemma claim Boston Marathon

Opinion

Opinion: Proposed height zoning change for Concord’s Main Street

Steve Duprey is the owner of the Duprey Companies The proposed zoning change to allow a 90-foot height building on Main Street, in appropriate cases, where the current zoning limits the height to 80 feet, makes sense and should be adopted. First, a...

Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down

Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down

Opinion: New Hampshire, it’s time to drive into the future

Opinion: New Hampshire, it’s time to drive into the future

Politics

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

As jury selection begins this week in the hush-money trial of former President Donald Trump, New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu says he doesn’t believe many voters view Trump’s criminal indictments, his actions on Jan. 6, 2021, or his election denialism...

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

Arts & Life

NH Furniture Masters present new member show this spring

The NH Furniture Masters are pleased to feature the work of three new members in our spring exhibition: Dan Faia, Mike Korsak, and Philip Morley. This exhibit celebrates the creativity and dedication of our newest members and brings together a diverse...

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

From the archives: Civil War brewing

From the archives: Civil War brewing

Obituaries

Arthur R. Stern

Arthur R. Stern

Belmont, NH - Arthur "Sonny" Stern, 82, passed on Friday, April 12, 2024, while returning from wintering in Florida. He was born on March 8, 1942, in Frederick Maryland. Sonny was the o... remainder of obit for Arthur R. Stern

Barbara J. McCaffrey

Barbara J. McCaffrey

Barbara J. (Smith) McCaffrey Concord, NH - Barbara J. (Smith) McCaffrey, died peacefully on Monday, April 15, 2024, at the age of 97, after a period of declining health. She was born in Conc... remainder of obit for Barbara J. McCaffrey

Larraine E. Butler

Larraine E. Butler

Loudon, NH - Larraine Butler, 77 years old, of Loudon, New Hampshire, passed away peacefully at home surrounded by her family. Larraine leaves behind her husband, James F. Butler, who she ... remainder of obit for Larraine E. Butler

Jane A. Haskell

Jane A. Haskell

Boscawen , NH - Jane A. Haskell, 95, died peacefully on Saturday April 13, 2024, at Merrimack County Nursing Home. She was born in Dover, NH, the daughter of Amy (Towle) and Harold Brow... remainder of obit for Jane A. Haskell

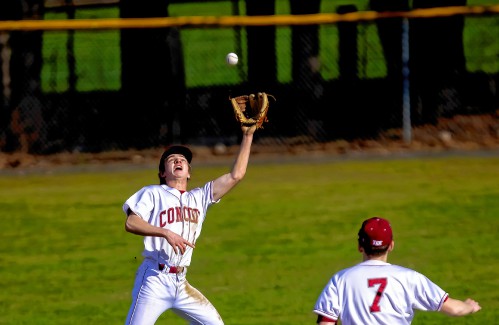

Wednesday’s high schools: Fancher’s 2-run blast leads Concord baseball to victory; plus more baseball, softball, lax and tennis results

Wednesday’s high schools: Fancher’s 2-run blast leads Concord baseball to victory; plus more baseball, softball, lax and tennis results

Softball: Maddy Wachter Ks 12, Concord holds off Winnacunnet in 2023 championship rematch

Softball: Maddy Wachter Ks 12, Concord holds off Winnacunnet in 2023 championship rematch

‘Money is a driver’: Amid inflation and tight labor market, city fighting to stem employee outflow

‘Money is a driver’: Amid inflation and tight labor market, city fighting to stem employee outflow

Wildfire season is here: Concord at moderate risk; high risk further south

Wildfire season is here: Concord at moderate risk; high risk further south

Court: Communities can’t reject solar on looks, property value fears alone

Court: Communities can’t reject solar on looks, property value fears alone

Mayors say need is growing for state homelessness prevention funds

Mayors say need is growing for state homelessness prevention funds

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success

Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation

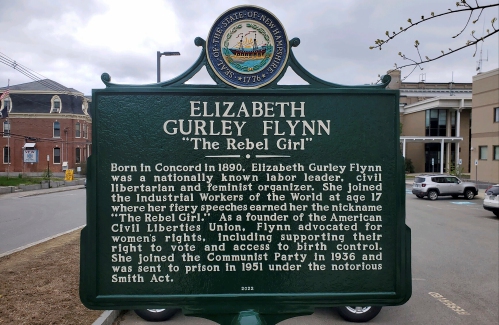

Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history

Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April

Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April