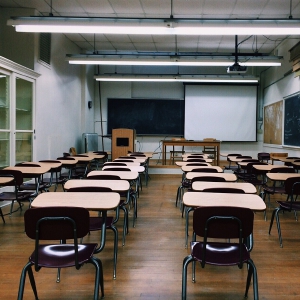

Students’ first glimpse of new Allenstown school draws awe

Jaws dropped and cheers erupted as Allenstown students entered their new school building for the first time Thursday morning.“Yo, this looks like a mall,” said an eighth grade boy in a Bruins shirt. “Smell that new school smell,” observed another.“We...

‘Bridging the gap’: Phenix Hall pitch to soften downtown height rules moves forward

Sue McCoo knew that adding flexibility to downtown zoning to allow for the repurposing of Phenix Hall would mean her store, Hilltop Consignment, would probably lose its longtime home on Main Street. The zoning change would open the door for the...

Most Read

Mother of two convicted of negligent homicide in fatal Loudon crash released on parole

Mother of two convicted of negligent homicide in fatal Loudon crash released on parole

Students’ first glimpse of new Allenstown school draws awe

Students’ first glimpse of new Allenstown school draws awe

Pay-by-bag works for most communities, but not Hopkinton

Pay-by-bag works for most communities, but not Hopkinton

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

‘Bridging the gap’: Phenix Hall pitch to soften downtown height rules moves forward

‘Bridging the gap’: Phenix Hall pitch to soften downtown height rules moves forward

Editors Picks

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Hometown Hero: Quilters, sewers grateful for couple continuing ‘treasured’ business

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Sports

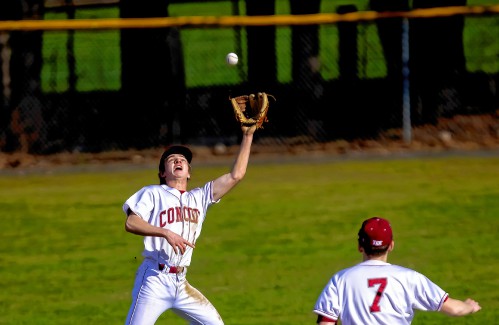

Softball: Maddy Wachter Ks 12, Concord holds off Winnacunnet in 2023 championship rematch

CONCORD — It wasn’t quite the high stakes of a state championship game at Memorial Field on Wednesday night, but Concord (3-0) knew that Winnacunnet (3-1) posed a good early-season test in its third game of the season.In a rematch of last year’s...

High schools: Tuesday’s track, baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

High schools: Tuesday’s track, baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

High schools: Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

High schools: Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

Opinion

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Todd Selig is the longtime town manager in Durham. Senate Bill 553 would require public funds from localities be invested in NH banks, where the NH Bankers Association, the lobbying arm for the banks, argues that according to a study it commissioned,...

Opinion: Proposed height zoning change for Concord’s Main Street

Opinion: Proposed height zoning change for Concord’s Main Street

Politics

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

As jury selection begins this week in the hush-money trial of former President Donald Trump, New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu says he doesn’t believe many voters view Trump’s criminal indictments, his actions on Jan. 6, 2021, or his election denialism...

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

Arts & Life

NH Furniture Masters present new member show this spring

The NH Furniture Masters are pleased to feature the work of three new members in our spring exhibition: Dan Faia, Mike Korsak, and Philip Morley. This exhibit celebrates the creativity and dedication of our newest members and brings together a diverse...

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

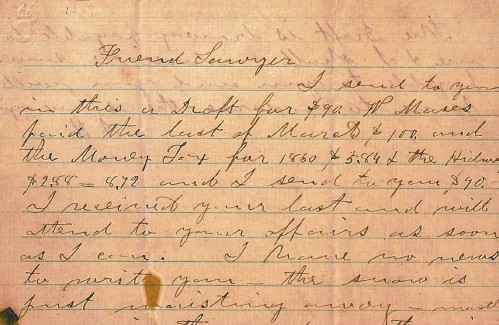

From the archives: Civil War brewing

From the archives: Civil War brewing

Obituaries

William J. Bruton

William J. Bruton

Concord, NH - William J. Bruton MD, of Concord NH and Harwich MA, previously of Summit NJ, died unexpectedly in Concord on Monday April 8. Dr. Bruton was member of Concord Orthopedics, ... remainder of obit for William J. Bruton

Franklin Cray

Franklin Cray

, Sr. Weare, NH - With heavy hearts, we bid farewell to a beloved husband, father, brother, Marine Corp Vietnam Veteran. He departed this world on April 15, 2024 leaving behind a legacy of l... remainder of obit for Franklin Cray

Bruce Sherwood Rogers

Bruce Sherwood Rogers

Concord, NH - Bruce Rogers, Born 9/19/1945 Newburyport Massachusetts. Passed on April 7th 2024 at Harris Hill Center, Concord, NH. He worked for Governors Academy, Byfield Mass. for 25 yea... remainder of obit for Bruce Sherwood Rogers

Harold Graham

Harold Graham

Woodsville, NH - Woodsville, NH - Harold "Jack" John Graham, 95, passed away at his home on Monday, April 15, 2024, with family at his side. He was born in his family home on Savage Hill in... remainder of obit for Harold Graham

Opinion: Adopting the right 306 Rules

Opinion: Adopting the right 306 Rules

After delay over neighbors’ concerns, Christ the King Food Pantry headed for rebuild

After delay over neighbors’ concerns, Christ the King Food Pantry headed for rebuild

Casinos can no longer charge rent to charities

Casinos can no longer charge rent to charities

Man granted parole for his role in the 2001 stabbing deaths of 2 Dartmouth College professors

Man granted parole for his role in the 2001 stabbing deaths of 2 Dartmouth College professors

‘I was scared:’ Meehan takes the stand in lawsuit alleging NH enabled child abuse at YDC

‘I was scared:’ Meehan takes the stand in lawsuit alleging NH enabled child abuse at YDC

‘It all feels so magical’: New England college students celebrate an LGBTQ prom at Dartmouth

‘It all feels so magical’: New England college students celebrate an LGBTQ prom at Dartmouth

Opinion: Being and becoming: A good doctor in the age of artificial intelligence

Opinion: Being and becoming: A good doctor in the age of artificial intelligence

Wednesday’s high schools: Fancher’s 2-run blast leads Concord baseball to victory; plus more baseball, softball, lax and tennis results

Wednesday’s high schools: Fancher’s 2-run blast leads Concord baseball to victory; plus more baseball, softball, lax and tennis results

Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success

Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation

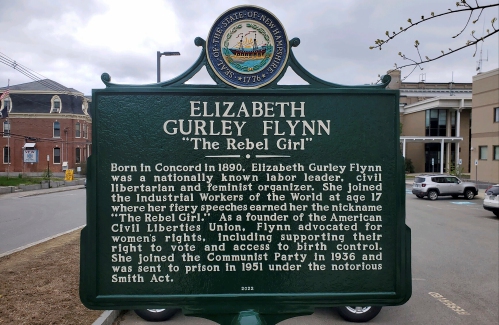

Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history

Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down

Opinion: How our twin toddlers turned our lives (and chairs) upside down Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April

Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April