Trauma-informed practices necessary for police, experts say

| Published: 07-01-2020 7:29 PM |

As calls to defund or reform the police grow nationwide and within New Hampshire, experts say trauma-informed training, which is sometimes intertwined with de-escalation training, is necessary within policing.

Trauma-informed practices – or practices that involve recognizing, understanding and properly responding to the effects of trauma – can be useful in police work beyond those situations, says Linda Douglas, NHCADSV’s trauma informed services specialist.

“It’s helpful for them to know why people are responding to them the way that they do. If you can understand that a person is behaving in a certain way because of trauma, then you may adjust your practices so that you’re not further escalating this person’s trauma,” Douglas said.

Understanding the root of a person’s behavior when it comes to interactions with police can aid officers in properly addressing the situation, rather than responding improperly.

“You should not only go into a situation thinking about how to de-escalate it, but what can you do not to make it any worse? The tone of your voice, the way that you approach, realizing that your presence, walking up to a group of people or walking up to a person could be scary to some people,” she added.

New Hampshire’s Police Standards and Training Council has a full day of training from the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence (NHCADSV) incorporated into its program. That training focuses on the impacts of domestic violence and sexual assault trauma on survivors. Some regional or local police departments request individual training sessions from their local crisis centers as well, but that is “very rare,” says Linda Douglas, NHCADSV’s trauma informed services specialist.

The state’s police officers also get six hours of “communications” training that addresses “de-escalation tools, effective listening skills and effective communication in a law enforcement setting,” according to a June 25 presentation by John Scippa, director of the council.

Douglas said she wishes she had more time to talk with officers about the lasting impacts of trauma.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Mother of two convicted of negligent homicide in fatal Loudon crash released on parole

Mother of two convicted of negligent homicide in fatal Loudon crash released on parole

Students’ first glimpse of new Allenstown school draws awe

Students’ first glimpse of new Allenstown school draws awe

Pay-by-bag works for most communities, but not Hopkinton

Pay-by-bag works for most communities, but not Hopkinton

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

Regal Theater in Concord is closing Thursday

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

‘Bridging the gap’: Phenix Hall pitch to soften downtown height rules moves forward

‘Bridging the gap’: Phenix Hall pitch to soften downtown height rules moves forward

“The police need training on so many things, it’s really hard to fit everything that they need training on,” she said.

During a normal day on the job, police may encounter people acting strangely or uncooperatively as a result of past traumatic experiences. Domestic violence survivors might not act in the exact way a police officer might expect them to: rather than crying, they might laugh or act detached when interacting with an officer. A child may have been exposed to or witness to the same domestic violence, which can cause lasting trauma.

Experts say that’s why trauma professionals need to work alongside police to make sure they are properly trained and prepared for these common encounters. It’s why Yale partnered with the New Haven Department of Police Service in 1991 to develop the Child Development-Community Policing Program (CD-DP). That program, composed of a team of child protective workers, mental health providers, police officers and other area professionals, is available 24/7 to answer police calls involving children who have witnessed or experienced violence.

Studies have shown that children exposed to violence in communities where the New Haven model exists receive more social, clinical and police services than children in communities without the program. The model is one New Hampshire has used to create its own trauma-informed policing services.

Manchester’s Adverse Childhood Experience Response Team (ACERT) has set out to make police and communities more versed in Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs. Born as a collaboration between Amoskeag Health and the Manchester Police Department in 2016, ACERT has referred over 1,200 children to services since its beginning, said Lara Quiroga, director of strategic initiatives for children at Amoskeag Health.

Training Manchester’s police force and first responders has been a major part of the initiative as well.

“Officers sometimes felt like they were leaving a home and the kids just didn’t have a chance, and they were worried that they would be seeing that kid again in 20 years on the other side of the law,” Quiroga said.

ACEs are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood and can include experiencing or witnessing abuse or growing up in an environment surrounded by substance use, mental health problems or household instability. A CDC study found that ACEs are strongly related to development of risk factors like disrupted brain development, depression and anxiety, and drug and alcohol abuse.

According to Nicole Rodler, chairperson of the New Hampshire Juvenile Court Diversion Network, youth in New Hampshire have gone through the state’s juvenile court diversion programs struggle with ACEs and mental health problems.

ACERT in Manchester is comprised of a police officer, a family advocate from Amoskeag Health, and a crisis services advocate from Manchester’s YWCA. The team goes out into the community three times per week to conduct follow-ups with families who may be in need of services, for example, if a police officer answered a domestic violence or overdose call at that residence a day earlier. If police receive a call that can be addressed by ACERT when they are out in the community, the team can respond to those scenes as well.

A family then has the choice to sign a release form that allows the appropriate agencies to reach out to those families directly, whether that be the YWCA, a local mental health center, or other local services.

The intent of an interaction with ACERT is not an arrest or a typical law enforcement interaction, Quiroga said, but to help families get the help they need.

“For the work that we do in Manchester around kids, our police department is very much visible in our community. Kids see school resource officers in their schools. They see police officers on the streets, driving in their cars. Some kids see friends or family having crime-related interactions with police,” Quiroga said. “The reality is that they are part of our community. And the reality is that they’re called to a variety of incidents and we want them to be prepared to respond to those incidents.”

Around one-third of families decline to sign the release that allows services to reach out to them, Quiroga said.

ACERT itself has served as a model to Concord and Laconia, both of which now have their own teams. Somersworth and Claremont are working on replicating it in their communities.

Concord Deputy Chief of Police John Thomas has been “blown away” by the success of the program. He told a story of a woman in the community who had a strong dislike for the police, but was able to get services to help her child through ACERT.

“I think being able to get in there at an early time to give these kids a chance to realize that this isn’t the way life is, that there’s other opportunities elsewhere, and people want to help them,” Thomas said.

Concord’s program began its operation in October of last year. According to Thomas, around 80% of people who had an interaction with ACERT signed the referral form to get services, but the success rate has sharply declined since COVID-19 spread through the state in March. Since then, the team has primarily reached out over the phone, but is planning to get back into the community next month.

Thomas and Quiroga both say the training that ACERT offers to police officers and other community organizations is applicable in a number of other interactions. The training not only explains the impacts of trauma on kids, but also how officers’ own trauma could influence their interactions with citizens.

“It’s also about, how do they specifically act? What are the things that are appropriate physically? What are you doing with your body that might feel threatening or increase the trauma? It’s really meant for every officer,” Quiroga said.

It is too soon to see the lasting effects of ACERT across the state. Its full impact may be understood years from now: whether the intervention provided has or has not been successful in preventing future outcomes. Quiroga says there is not currently enough funding available for a long-term study of that scope, but other programs that ACERT has used as a model have shown success.

ACERT Manchester gets a total of $650,000 per year in federal and local grants – not taxpayer dollars – which covers services, training, wages and benefits. City aldermen recently passed a city budget that included over $27 million for its police department.

Services like ACERT – while they can help serve as a preventative measure of future crime and help people access social services – are not part of the police defunding model that some activists have been calling for. The programs in Manchester and Concord both operate on separate grant funding while police continue to operate on their own budget.

“What people don’t realize is, the people who are saying that are not the people on the ground doing the work,” Thomas said. “In the real world you’ll never be able to fully take [policing] away.”

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.

]]>

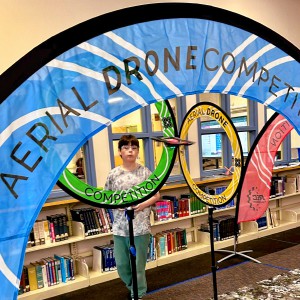

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure

Granite Geek: Forest streams are so pretty; too bad they’re such a pain to measure