Latest News

Vandals hit mausoleum of Tilton's namesake

Vandals hit mausoleum of Tilton's namesake

Opinion: Adopting the right 306 Rules

Opinion: Adopting the right 306 Rules

What’s in a name? Ask an Epsom Yeaton.

Norm Yeaton dropped a stack of papers three inches thick, attached by a clip, onto his living room table.The thud said a lot, that an arduous research project by Yeaton – in an attempt to understand the sheer volume of people in Epsom whose last name...

‘We’re just kids’: As lawmakers debate transgender athlete ban, some youth fear a future on the sidelines

Maëlle Jacques has read the articles written about her.“Winner of NH Girls High Jump is Biological Male.”“Transgender girl blasted after dominating New Hampshire girls high jump.”“U.S. ‘Full of Failing Gutless Mothers and Fathers’: High School Boy...

Most Read

Editors Picks

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Concord martial arts studio builds life skills far beyond combat

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

Red barn on Warner Road near Concord/Hopkinton line to be preserved

FAFSA fiasco hits New Hampshire college goers and universities hard

FAFSA fiasco hits New Hampshire college goers and universities hard

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Searchable Concord salary database: Top earners include more police, fewer women

Sports

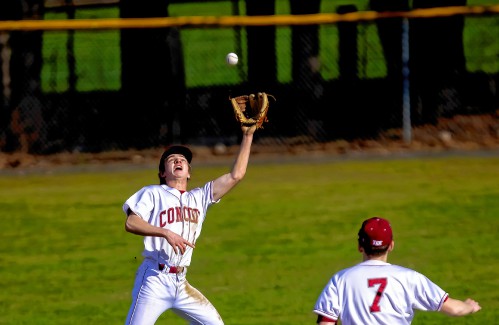

Wednesday’s high schools: Fancher’s 2-run blast leads Concord baseball to victory; plus more baseball, softball, lax and tennis results

BaseballConcord 9, Winnacunnet 8Key players: Concord – Matt Jenness (winning pitcher), Jackson Martin (save), Mitch Coffey (3 hits, 2 runs, RBI), Dawson Fancher (2-run HR, 2 hits, 2 runs, 3 RBI), Brett McDonough (2 hits, 2 RBI), Kaelen Williams (hit,...

Opinion

Opinion: Being and becoming: A good doctor in the age of artificial intelligence

Narain Batra, under the auspices of the Osher Institute at Dartmouth, will deliver a public lecture, “Superintelligence: Why We Need It” on May 24. He lives in Hartford, Vermont. A few years ago, I was on a return flight from New Delhi to Paris and...

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Opinion: Bankers have the NH Public Deposit Investment Pool in their sights

Opinion: Proposed height zoning change for Concord’s Main Street

Opinion: Proposed height zoning change for Concord’s Main Street

Politics

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

As jury selection begins this week in the hush-money trial of former President Donald Trump, New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu says he doesn’t believe many voters view Trump’s criminal indictments, his actions on Jan. 6, 2021, or his election denialism...

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

League of Women Voters suing over AI robocalls sent in NH

Arts & Life

NH Furniture Masters present new member show this spring

The NH Furniture Masters are pleased to feature the work of three new members in our spring exhibition: Dan Faia, Mike Korsak, and Philip Morley. This exhibit celebrates the creativity and dedication of our newest members and brings together a diverse...

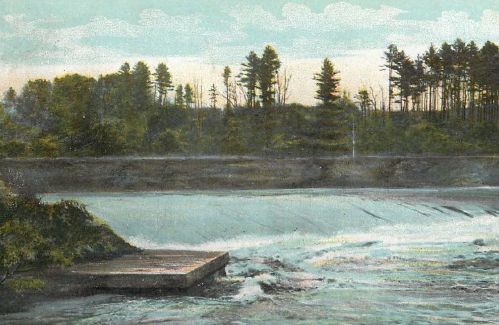

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

Vintage Views: The greatest factory that never was

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

Inspired by Robert Frost, New Hampshire Poet Laureate Jennifer Militello has achieved her childhood dreams

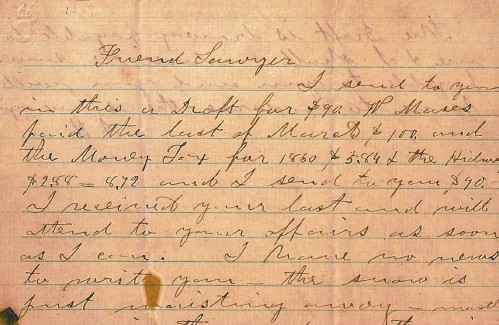

From the archives: Civil War brewing

From the archives: Civil War brewing

Obituaries

Allen C. Cole

Allen C. Cole

Allan C. Cole Pembroke, NH - Allan C. Cole, 87, of Pembroke, passed away on Wednesday March 27, 2024 at Concord Hospital following a period of declining health. Allan was born on Novembe... remainder of obit for Allen C. Cole

Kirsten Wirth

Kirsten Wirth

Concord, NH - Kirsten Wirth passed from this life peacefully after a brief battle with cancer, with three of her siblings surrounding her with love at her bedside in Concord, NH on March 29... remainder of obit for Kirsten Wirth

Cynthia Grudak

Cynthia Grudak

Hayesville, NC - Cynthia Charles Grudak 84, of Murphy, North Carolina passed away Tuesday, April 9, 2024, in a Clay County care facility. She was the daughter of the late Harold and Louise... remainder of obit for Cynthia Grudak

Kevin Ward Jenkins

Kevin Ward Jenkins

Concord, NH - Kevin Ward Jenkins, 67, died Friday, April 12, 2024 at Concord Hospital, Concord, NH. Born on April 3, 1957 in Concord, NH, Kevin is the son of the late Ward and Charlene ... remainder of obit for Kevin Ward Jenkins

On the trail: NH GOP leaders urge ‘decorum and respect’

On the trail: NH GOP leaders urge ‘decorum and respect’

From a book to bread, Merrimack Valley High School students show off their senior projects

From a book to bread, Merrimack Valley High School students show off their senior projects

Beekeepers, farmers square off in NH Senate committee hearing

Beekeepers, farmers square off in NH Senate committee hearing

Gallery: Forty-mile gravel bicycle race draws racers from all over the region

Gallery: Forty-mile gravel bicycle race draws racers from all over the region

The fraught path forward for cannabis legalization, explained

The fraught path forward for cannabis legalization, explained

Mother of two convicted of negligent homicide in fatal Loudon crash released on parole

Mother of two convicted of negligent homicide in fatal Loudon crash released on parole

Softball: Maddy Wachter Ks 12, Concord holds off Winnacunnet in 2023 championship rematch

Softball: Maddy Wachter Ks 12, Concord holds off Winnacunnet in 2023 championship rematch High schools: Tuesday’s track, baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

High schools: Tuesday’s track, baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success

Boys’ lacrosse: With a different level of energy and focus, MV feels primed for success Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss

Baseball: Concord makes eight errors but shows reasons for optimism in wild extra-inning loss Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation

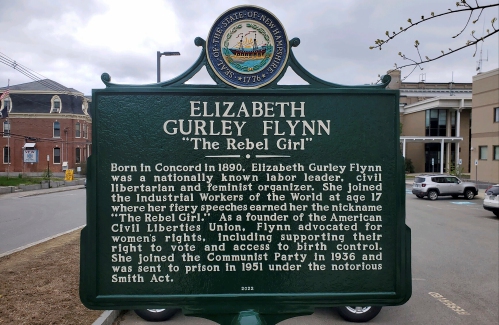

Opinion: Members of NH Jewish community write letter to NH congressional delegation Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history

Opinion: Whatever a court decides, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn retains an important place in American labor history Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April

Sunapee Kearsarge Intercommunity Theater presents ‘Olympus On My Mind’ in April