Opinion: Who deserves a peace prize?

| Published: 05-02-2025 7:23 PM |

Randall Balmer, who teaches at Dartmouth College, is writing a biography of Mark O. Hatfield.

Donald Trump apparently covets the Nobel Peace Prize. (I confess something feels wrong about that sentence, apart from any consideration of whether or not he might be worthy. It seems, well, unseemly for someone to covet the Nobel Peace Prize.)

But that’s the gist of reporting by Tyler Pager in The New York Times. Trump has groused often and at length that he has yet to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, angered that two of his predecessors, Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama, have been so honored.

He finds the Obama case especially galling — but Trump has been obsessed with Obama for more than a decade, beginning with the “birther” nonsense that the 44th president was not born in the United States. Obama, you’ll recall, was awarded the prize early in his presidency, and he accepted it with humility, averring that his “accomplishments are slight” in comparison with other Peace Prize winners.

But humility, as we’ve learned, is not in Trump’s playbook. “If I were named Obama, I would have had the Nobel Prize given to me in 10 seconds,” he complained in a speech to the Detroit Economic Club last October.

His acolytes quickly fell into line. Steven Cheung, White House communications director, said, “The Nobel Peace Prize is illegitimate if President Trump — the ultimate peace president — is denied his rightful recognition of bringing harmony across the world.”

Well, let’s see. The “ultimate peace president” did promise to end the Russia-Ukraine War on the first day of his second term in office. Quite a few days have passed, and yet the war continues. He hosted — and promptly humiliated — Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s president, in the Oval Office and proceeded to conduct negotiations about Ukraine’s future while denying Ukraine a place at the table.

As for ending the war in Gaza, Trump’s apparent solution is to turn Gaza into a resort. Trump’s drive-by diplomacy stands in stark contrast to previous prize winners.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

With Steeplegate still held up in court, city privately debates public investment

With Steeplegate still held up in court, city privately debates public investment

Sudden pile of trash near Exit 13 on Manchester Street in Concord considered ‘illegal dumping’

Sudden pile of trash near Exit 13 on Manchester Street in Concord considered ‘illegal dumping’

‘Peace of mind’: As New Hampshire nixes car inspections, some Concord residents still plan to get them

‘Peace of mind’: As New Hampshire nixes car inspections, some Concord residents still plan to get them

Mullet madness: Young man who died in motorcycle accident remembered at local fundraiser

Mullet madness: Young man who died in motorcycle accident remembered at local fundraiser

State budget mandates sale of mental health housing in Concord

State budget mandates sale of mental health housing in Concord

OSHA investigates Pittsfield partial building collapse

OSHA investigates Pittsfield partial building collapse

Whereas Obama was cited for his efforts to forestall and to reverse climate change, Trump has directed his administration to reverse those reversals.

When Carter won the 2002 prize for opposing George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, he was also cited for brokering the Camp David Accords between Israel in Egypt in 1978. As Lawrence Wright’s Thirteen Days in September demonstrates, Carter was tireless in his efforts to bring Egypt’s Anwar el-Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin to terms. He worked late into the night, shuttled between the two delegations at Camp David, wheedled and cajoled — and finally won a landmark treaty between the presidents of two ancient enemies.

Trump may yet find his footing as a peacemaker, but I wouldn’t count on the people of Panama or Greenland to second the nomination.

And here’s a tip: If you’re serious about being regarded as a peacemaker, perhaps you should reconsider dismantling the United States Institute of Peace.

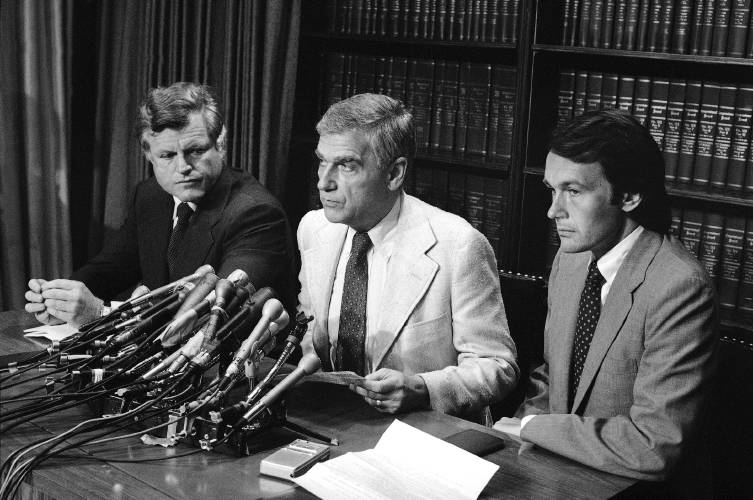

The idea for the institute originated with Mark O. Hatfield, Republican senator from Oregon, who served from 1967 to 1997. Hatfield was among the first GIs to enter Hiroshima after the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb in 1945.

The survivors he encountered were wary, but they were also hungry. When one member of the crew broke out his sack lunch and shared it with those who, days before, were considered enemies, Hatfield and others did the same in a scene reminiscent of Holy Communion. “I lifted up a small Japanese child and was purged, spiritually renewed as hate flowed from my system,” Hatfield recalled.

Hatfield stopped short of calling himself a pacifist, but he harbored deep suspicions of armed conflict. He never supported a military spending bill, even as chair of the Appropriations Committee. He also reasoned that if the United States could spend billions every year to stoke the engines of warfare, it could also afford to spend a bit of money looking for ways to promote peace.

In 1984, Ronald Reagan signed a bill authorizing the Institute of Peace, with a mission to “promote international peace and the resolution of conflicts among the nations and peoples of the world without recourse to violence.”

The institute is funded by Congress, but it is independent and not for profit. It offers training for diplomats and peace negotiators, and it provides briefings for Congress.

The Peace Prize aspirant, however, objected. On March 14, the Trump administration fired all 10 members of the institute’s board — five Republicans and five Democrats — and Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency attempted to enter the building forcibly to oust the institute’s acting president.

After a standoff and with the help of Washington Metropolitan Police, the DOGE forces successfully breached the building and installed Kenneth Jackson, a State Department official who had helped dismantle the U.S. Agency for International Development, as president of the Peace Institute. Trump proceeded to fire nearly all of the institute’s employees.

All in all, not a good look for someone who covets the Nobel Peace Prize.

Opinion: Trumpism in a dying democracy

Opinion: Trumpism in a dying democracy Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today Opinion: The art of diplomacy

Opinion: The art of diplomacy Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community

Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community