Latest News

Hometown Heroes: Couple’s sunflower fields in Concord reconnects the community to farming

Whether they’re running errands or socializing in the community, Greg Pollock and Amber Brouillette, are recognized as “the sunflower people” by Concord residents thanks to their Sunfox Farm, a sprawling 20-acre sunflower field on Loudon Road, that...

Storm drain issue stalls Stickney Ave housing project

Plans to transform the dilapidated former Department of Transportation buildings off Stickney Avenue into 80 housing units have been held up because of outstanding questions about the condition and future of major city storm drains running underneath...

Most Read

Hometown Heroes: Couple’s sunflower fields in Concord reconnects the community to farming

Hometown Heroes: Couple’s sunflower fields in Concord reconnects the community to farming

Boscawen resident takes issue with proposed town flag designs

Boscawen resident takes issue with proposed town flag designs

Skepticism turns to enthusiasm: Concord Police welcome new social worker

Skepticism turns to enthusiasm: Concord Police welcome new social worker

With new plan for multi-language learners, Concord School District shifts support for New American students

With new plan for multi-language learners, Concord School District shifts support for New American students

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

Opinion: The Concord School Board can restore trust with residents

Opinion: The Concord School Board can restore trust with residents

Editors Picks

What’s in a name? Ask an Epsom Yeaton.

What’s in a name? Ask an Epsom Yeaton.

Downtown cobbler breathes life into tired shoes, the environmentally friendly way

Downtown cobbler breathes life into tired shoes, the environmentally friendly way

People of color incarcerated at higher rates in New Hampshire, but data is limited

People of color incarcerated at higher rates in New Hampshire, but data is limited

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

Sports

High schools: Bow track sweeps 4-team meet at Pembroke

Boys’ TrackBow 87, John Stark 57, Pembroke 43, Manchester West 34Key players: Bow – Kody McCranie (1st 100, 1st 200, 1st 400, 1st long jump), Wyatt Worcester (1st 1,600, 1st 3,200), Colin Atwell (1st high jump, 2nd 300 hurdles, 5th triple jump), Liam...

Opinion

Opinion: Campus chaos and America’s character

Vikram Mansharamani of Lincoln is a candidate for Congress in New Hampshire’s 2nd Congressional District. He was previously on the faculties of both Yale and Harvard. Jewish students being warned to avoid college campuses for their own safety. Angry...

Opinion: Learning from landscapes

Opinion: Learning from landscapes

Opinion: ‘This being human is a guest house’

Opinion: ‘This being human is a guest house’

Opinion: The truth of it

Opinion: The truth of it

Politics

Charities will not have to pay rent to casinos under new law

Deb Leahy can finally breathe easy, freed from the fluctuating rental fees each time her organization partners with a New Hampshire casino for donations.Thanks to a new law, casinos are now prohibited from imposing rent charges on charities for...

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

Arts & Life

Concord Chorale presents ‘The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace’ by Karl Jenkins

Concord Chorale presents The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace by Karl Jenkins on May 4 and 5 at St. Paul’s Church in Concord.A Mass for Peace was composed by Karl Jenkins in 1999 as a tribute to the victims of the Kosovo crisis. The timeless text of this...

Vintage Views: Our beloved May Day with dancing, horn blowing

Vintage Views: Our beloved May Day with dancing, horn blowing

Homeyer: Tips for planning a successful garden

Homeyer: Tips for planning a successful garden

From the farm: The Cow Spa is open

From the farm: The Cow Spa is open

Obituaries

Charles E. Lavalley Jr.

Charles E. Lavalley Jr.

Charles E. Lavalley, Jr. Allenstown, NH - Charles E. Lavalley, Jr, 95, passed away on Thursday, April 18, 2024 following a period of declining health. He was born on June 19, 1928 in Philadelphia, PA to the late Charles E. and Mary R. (B... remainder of obit for Charles E. Lavalley Jr.

Clyde R.W. Garrigan

Clyde R.W. Garrigan

Concord, NH - Clyde Richard Wendell Garrigan, of Concord, NH passed away on Sunday, April 21, 2024. He was born on June 3, 1953 in Brooklyn, NY to Patrick and Barbara Garrigan. He was raised in Valley Stream, NY and graduated from Valle... remainder of obit for Clyde R.W. Garrigan

Joanna M. Cloe

Joanna M. Cloe

formerly of Pembroke, NH - Joanna Mary (Cavanagh) Cloe, 79, passed away in Florida April 17th after a short illness. She was formerly a longtime resident of Pembroke, NH and member of St. John the Baptist Church. She was born in Bat... remainder of obit for Joanna M. Cloe

Rita A. French

Rita A. French

Contoocook, NH - Rita A. French, age 98, of Park Ave, passed away peacefully on Monday, April 22, 2024 at her home. She was born in Barton, VT one of 7 Children to the late Samuel and Myra (Leonard) Paul. Rita worked at Concord Hos... remainder of obit for Rita A. French

Former HR head testifies to ‘94 investigation into abuse at NH youth detention facility

Former HR head testifies to ‘94 investigation into abuse at NH youth detention facility

Senate weighs farm-to-school pilot program

Senate weighs farm-to-school pilot program

Opinion: No, Republicans are not better on the economy

Opinion: No, Republicans are not better on the economy

Electric school buses are about to hit the road in Henniker and Weare

Electric school buses are about to hit the road in Henniker and Weare

Track: Concord girls win 46-team Black Bear Invitational, Goulas and Twite sets meet records in triple jump

Track: Concord girls win 46-team Black Bear Invitational, Goulas and Twite sets meet records in triple jump

High schools: Weekend baseball, softball and lax results

High schools: Weekend baseball, softball and lax results

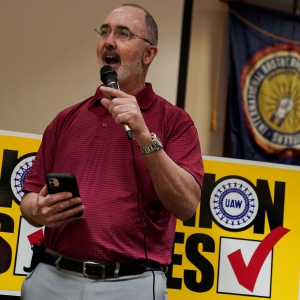

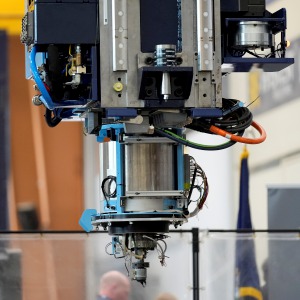

The world’s largest 3D printer is at a university in Maine. It just unveiled an even bigger one

The world’s largest 3D printer is at a university in Maine. It just unveiled an even bigger one

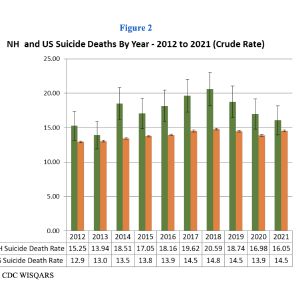

Suicide rates in New Hampshire declining since 2018, report says

Suicide rates in New Hampshire declining since 2018, report says

High schools: Concord girls’ lax picks up first win, Tide softball handed first loss in pitchers’ duel

High schools: Concord girls’ lax picks up first win, Tide softball handed first loss in pitchers’ duel High schools: Coe-Brown softball wins 5th straight, Concord’s McDonald pitches first varsity win, Tide’s Doherty scores 100th career point

High schools: Coe-Brown softball wins 5th straight, Concord’s McDonald pitches first varsity win, Tide’s Doherty scores 100th career point High schools: Bow’s Kelly lifts Falcon softball to victory in walk-off, more Monday results, plus Saturday’s track meets

High schools: Bow’s Kelly lifts Falcon softball to victory in walk-off, more Monday results, plus Saturday’s track meets Patriots’ draft approach likely to be different in post-Belichick era

Patriots’ draft approach likely to be different in post-Belichick era Opinion: Summer camp registration: The only thing higher than the price is the anxiety

Opinion: Summer camp registration: The only thing higher than the price is the anxiety Celebrate agriculture, education, and community at the NH Farm, Forest, and Garden Expo

Celebrate agriculture, education, and community at the NH Farm, Forest, and Garden Expo