Remembering Bobbie Miller: 14 years after her murder, family seeking answers from investigators

|

Published: 03-21-2024 3:43 PM

Modified: 03-22-2024 11:48 AM |

Maddie Dionne smiled her way through much of a 90-minute conversation when speaking about life’s simplest things.

They’ve taken on greater importance over the past 14 years.

She has coffee with her son, Ken Dionne, each morning in New Boston, sitting on the family’s deck that wraps around a wood-paneled home, a masterpiece, like a veranda in the Deep South.

She leaves Ken a breakfast sandwich in the morning, always on the kitchen table, and Ken says that no matter how early he rises, the sandwich is always there, waiting.

She flipped through a photo album, pointing to photos of her daughter, Bobbie Miller, who was shot and killed at her home in Gilford 14 years ago in what remains a cold case. The memories kept coming about how adventurous Bobbie was, like the time she and a friend moved to Arizona soon after graduating from Manchester West High School. No plans. Just go.

Thinking about Bobbie each morning, she blasts a family-wide email with various messages, like, “Hope you enjoy your day. Tomorrow I will send another. Love you all.”

It’s one way to ease the hurt that few experience.

“Every morning I look at Bobbie’s picture and I say the prayer and give her a kiss,” Maddie Dionne said. “Every morning. Every morning.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

No deal. Laconia buyer misses deadline, state is out $21.5 million.

No deal. Laconia buyer misses deadline, state is out $21.5 million.

Quickly extinguished fire leaves Concord man in critical condition

Quickly extinguished fire leaves Concord man in critical condition

Concord police ask for help in identifying person of interest in incidents of cars being keyed during Republican Party event

Concord police ask for help in identifying person of interest in incidents of cars being keyed during Republican Party event

Update: Victim identified in Lantern Lane fire in Concord

Update: Victim identified in Lantern Lane fire in Concord

She’s 94 and still drives herself to the grocery store. Ken, 66, is a retired building contractor who built the secluded home that includes a living room with an 18-foot-high ceiling and a panoramic view of trees and mountains.

He lives with his mother and his wife, Candace Dionne. He’s a big-game hunter and former taxidermist. He’s also the high-octane fuel behind the movement seeking to find the person who killed his sister on that Halloween day in 2010, which has become a full-time job these days. He watches over the moves by the Attorney General’s Office like the 1,300-pound Kodiak bear – killed by Ken in Alaska using a bow – that stood on all fours, just behind his head.

He says he was diplomatic for a while, sympathetic toward the prosecutors and detectives who have the difficult jobs of working on a cold case. But like other families who are dealing with a lingering unresolved crime, he’s grown impatient. “The gloves are off,” he said last week as he cited his biggest issue – a lack of communication.

He once sent an email to the AG’s Office, saying, “I can’t believe I can’t even get the decency of a phone call or an email from you guys. I hope you enjoy your tenure until you can punch your clock and collect your retirement.”

He blames short staffing, or lack of funding, or broken promises, or incompetency, or people who give you lip service and nothing more.

His sister, a mother of two, was 54 when she was shot to death on Oct. 31, 2010, in the ranch-style home she had just purchased in Gilford after a difficult divorce. She lived alone. Her golden retriever, Sport, was shot and killed as well.

No arrests have been made as the years passed. Suspicion quickly fell on Bobbie’s ex-husband, but he passed a lie detector test and his alibis and interviews convinced police he wasn’t their man.

Ken has become part of a select group of family victims, desperate for information about disappearances or unsolved murders of loved ones. They gained momentum recently, rallying at the Department of Justice last summer to draw attention to the 130 or so cold cases in this state that in their minds are more than just cold: they’re closed.

“You can only get slapped in the face so many times before you say I am tired of getting slapped in the face,” Ken said. “It’s easier now that I am retired and can spend more time on it and I want to turn up the heat.”

They want publicity – lots of it – to stoke the fire and keep the stories in the headlines, in hopes of gathering information from the Cold Case Unit, motivating them to work harder and loosening up funding to expand the staff.

Meanwhile, no one has been more zealous than Ken. He’s out front, armed with a manilla folder four inches thick, stuffed with seemingly every correspondence he’s had with the Attorney General’s Office over the years.

He hasn’t been shy about accusing someone, a family member, and criticizing law enforcement for not doing enough to solve the case.

Michael Garrity, the director of communications for the Attorney General’s Office, relayed feedback from his boss, Attorney General John Formella, who said the agency hired new people specifically to work cold cases.

“Fortunately,” Garrity said in an email, “we have seen increasing resources for the Attorney General’s Cold Case Unit.”

That’s good news, Ken said, but the plan he was told – hiring two full-timers – has morphed into a pair of law enforcement officials who investigate other crimes, not just the unsolved ones.

The comments that commonly emerge from the AG’s Office, via phone calls or emails from Garrity, have done little to appease people like Ken and Maddie and more than 100 other family victims of cold case tragedies.

“While we cannot share specific additional information about the case to preserve the integrity of the investigation, our detectives and prosecutors are always seeking new leads from the public,” Garrity wrote.

Ken rolls his eyes at input like that. He invited ABC’s 20-20 news program to visit the state to document the Cold Case system here.

“It’s not about my sister’s case but embarrassing the state of New Hampshire and how inept we are,” Ken said.

The mood lightened quickly when the topic changed to Bobbie the person, not Bobbie the statistic. Big sister Bobbie, one of five girls, was 13 months older than Ken. They’d walk home from Manchester West and invariably get a ride.

“We might walk now and then and all the boys had crushes on Bobbie,” Ken said. “They’d always stop.”

She loved sewing, dirt biking, hiking, sailing. She was easy going but was apt to swing her pocketbook your way when upset. She worked for her ex-husband’s successful car dealership and had money from the divorce settlement. They raised two kids.

“She was artsy craftsy,” Ken said. “She stained glass. She stained glass with that deer on it and we found it at her house and brought it here. We think she was making it for us for Christmas.”

The stained glass in the living room is a reminder of something good, wrapped in sadness. Maddie sends her little messages to family each morning, after a hug from Ken Wife’s, Candace. This day happened to be warm outside, framed nicely by the view from the deck, where mother and son have coffee on calm mornings.

“Good morning, everyone. It’s a beautiful, sunny morning. Enjoy your day.”

The Cold Case Unit’s investigation into the circumstances of the October 2010 homicide of Miller is still open and pending new investigative leads. While cold case investigations are some of the most difficult investigations, public assistance can make all the difference, according to the Attorney General’s Office.

Anyone who has any information about the circumstances surrounding Miller’s murder is urged to contact the Cold Case Unit at (603) 271-2663 or submit information through the Attorney General’s Office Cold Case Unit website at https://www.doj.nh.gov/criminal/cold-case/tip-form.htm.

“Even the smallest observation could provide a piece of the puzzle necessary in solving this act of violence,” the Attorney General’s Office said. “This is especially true for anyone who saw or spoke with her between 4 p.m. on Sunday, October 31, 2010, and 5 p.m. on Monday, November 1, 2010.”

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game

Voice of the Pride: Merrimack Valley sophomore Nick Gelinas never misses a game With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer

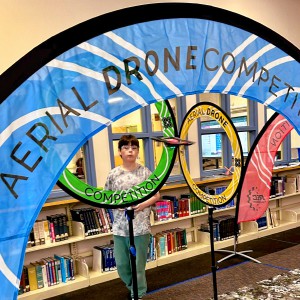

With less than three months left, Concord Casino hasn’t found a buyer Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition

Kearsarge Middle School drone team headed to West Virginia competition Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda

Phenix Hall, Christ the King food pantry, rail trail on Concord planning board’s agenda