As site testing begins on new middle school site, activists file to put location debate on the ballot

|

Published: 05-15-2024 5:05 PM

Modified: 05-16-2024 10:43 AM |

In the woods off South Curtisville Road, between maple saplings and tall pines and within sight of dog walkers on trails, fifteen wooden stakes flagged with hot pink construction tape poke up from the pine needles carpeting the ground.

The stakes mark locations where a team of engineers bored more than 30 feet into the ground for soil testing: nine of them dot the proposed footprint of Concord’s new middle school. The samples will help engineers determine how expensive it will be to put a foundation for a 140,000-square-foot structure on the raw land. Preliminarily, they liked what they found: the soil is sandy and the land flat.

Outside the homes in the surrounding neighborhoods, white signs dotting the grassy front lawns stand in contrast, demanding that construction happen elsewhere. “Rescind the vote to build at Broken Ground,” the placards plead. “Rebuild at Rundlett!”

As the school board, its committees and its architects work toward a final design and updated price tag for the new school, an activist group has filed petitions that would force the board to get voter approval on the relocation of any school – restricting the school board’s power and un-doing its December vote not to rebuild at Rundlett.

“We want to prove that the voting populace can take back some control,” said Jeff Wells, a founding member of Concord Concerned Citizens. “We want to make this right.”

After months of unsuccessfully lobbying the board to reverse its decision to locate the new middle school on the east side of the city, the Concerned Citizens issued an ultimatum last month, threatening to strip the school board of its autonomy if it did not reconsider.

When it issued that threat, the group was considering three potential amendments to the district’s charter: one would require the annual school budget to get direct approval from voters, another would put any school capital projects over $50 million on the ballot, and a third would remove the autonomous governance structure of the board altogether.

The two amendments the group ended up drafting and submitting to the district and state for review, however, are more tempered and more surgical. Rather than going after the budget process, they are tailored to try to overturn the Broken Ground site vote and prevent the sale of the current Rundlett property — which many still believe is the only appropriate location for the new middle school.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Sudden pile of trash near Exit 13 on Manchester Street in Concord considered ‘illegal dumping’

Sudden pile of trash near Exit 13 on Manchester Street in Concord considered ‘illegal dumping’

With Steeplegate still held up in court, city privately debates public investment

With Steeplegate still held up in court, city privately debates public investment

Merrimack Valley schools to consider eliminating most Penacook bus routes

Merrimack Valley schools to consider eliminating most Penacook bus routes

Blueberries, honey, flowers and more: Dunbarton gets a new farmers’ market

Blueberries, honey, flowers and more: Dunbarton gets a new farmers’ market

OSHA investigates Pittsfield partial building collapse

OSHA investigates Pittsfield partial building collapse

Traffic declined at Manchester Airport last year, making it the only major airport in New England that failed to grow

Traffic declined at Manchester Airport last year, making it the only major airport in New England that failed to grow

“We talked about it, and we’re not in it to blow things up,” Wells said when asked about the shift. “We’re not about wrecking the charter, taking away their responsibilities… We want to make some corrections.”

If passed, these amendments would require the relocation of any school from its address at the start of this year and the sale of district land to be endorsed by the voters through a ballot measure.

Unlike other school districts in New Hampshire, Concord’s School Board is autonomous, meaning it has the final say over decisions like budgets, collective bargaining agreements and bonds that elsewhere would go before a city council or town meeting. That autonomy is laid out in its charter, which can be amended in multiple ways. Voter-led changes need to be drafted by a committee, get legal review by the state, and win signatures from 15% of the number of voters from the last election to be placed on a ballot, per RSA 49-B. Ballot amendments have to win more than 60% of the vote to pass, per the charter.

In a response letter filed with the state, an attorney for the district argued that the proposed amendments would violate state law by acting retroactively and creating an authorized governance structure.

State law does not provide for city governments to take on town meeting-style where voters have direct approval power, Attorney Dean Eggert wrote. “Any such new municipal creature, if lawful, would require an enabling act of the legislature and subsequent ratification by the citizens.”

Additionally, Eggert argued, RSA 199 makes the board’s decision on the location of any school final for five years unless voters appeal the decision as laid out in the law, which they have not. Section nine of the law states that 10% of voters, if “aggrieved by the location of a schoolhouse by the district or its committee, or by the school board,” may appeal the decision to the state Board of Education within 10 days.

RSA 199:8 — not cited in Eggert’s letter — allows the same portion of voters to file an appeal directly with the school board, forcing it to hold a new hearing and reconsider the location. Neither type of appeal has been pursued.

Thirdly, Eggert argues, allowing the amendment to apply to the middle school would violate the states legal precedent banning retroactive laws, violating its architectural and pre-construction contracts and threatening Concord’s eligibility for school building aid.

However, the district’s building aid application was based on a previously-considered Clinton Street location. Concord will need to be ready for construction and have secured local funding to accept an aid offer when it comes, which would be in the second half of next year.

When responding to complaints about the $176 million price tag for the new middle school, board members have maintained they have simply voted to design, not build a new middle school and final approval for the project is still ahead.

Reversing the location decision for the middle school would not only be expensive, according to Board President Pamela Walsh, but would delay the project’s schedule. Walsh claimed that delay would be “five or more years.”

If the district is not prepared to accept aid next fall, it can pass on the state’s initial offer and remain first in line for the next one — the district built a contingency for not getting timely aid into its $10 million contract with the project’s architects.

State officials have about a month to issue insights on the legality of the proposed amendment language. The Concerned Citizens group, founded in February, began its campaign for the school board to re-open its location debate — hoping that membership changes on the board would flip the outcome — with an online petition. The petition currently has nearly 1,300 signatures, but no board member yet has moved for reconsideration, including those who opposed the new site.

Despite these defeats, and as project planning has moved forward, members have continued to publicly push for a re-vote, increasingly focusing their arguments on conservation concerns. They believe that building anew — clearing land for a new school behind the elementary schools in East Concord instead of reconfiguring the current, already-developed site on South Street — would mean an unnecessary culling of forest with recreational and environmental importance.

“We’re making a decision that flies in the face of responsible stewardship: rather than using land that already is cleared and has the necessary infrastructure for a middle school, we’re choosing to build one of our fragile and rapidly vanishing woodlands,” Ellen Kenny, a longtime Concord elementary school teacher, said at the April meeting. “If the vote is not rescinded, Concord’s young students at Broken Ground and Mill Brook will have a front row seat to habitat destruction and ‘do as I say, not as I do’ adult hypocrisy.”

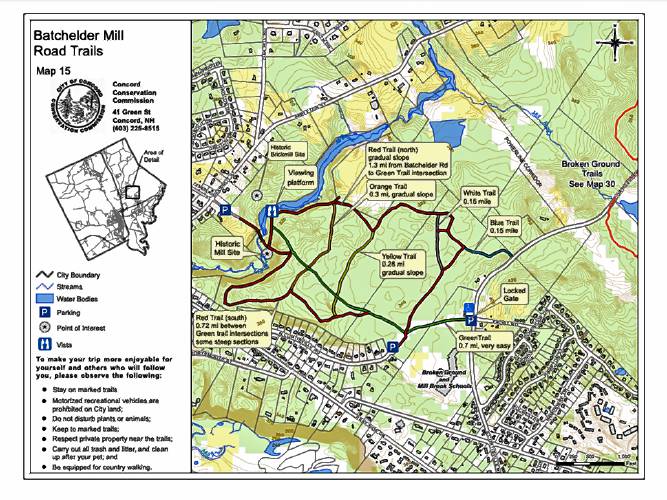

Current plans place the new school atop some hiking trails, which will require them to be rerouted.

District students “are being educated about sustainability of the environment,” Steve Michlovitz said at the May meeting last week, noting the district’s Earth Day programming. “They are questioning their teachers and parents about why acres of mature-growth pine forest on the school district’s Broken Ground property are going to be cut down to clear a site for a new middle school when a perfectly suitable location already exists that will eliminate the need to destroy a single tree.”

As the working school designs have evolved, putting proposed athletic facilities deeper into the district’s acreage, the amount of clearing proposed has jumped. When the school board selected the site last year, it cited roughly eight acres of tree clearing that would need to take place out of the district’s 59-acre plot. While the number and size of athletic fields at the new school are still being workshopped, the amount of tree clearing on the school’s land in the most recently presented designs is up to 19 acres, according to project architects. One of the items most debated on the district’s planning committees is whether to include the baseball and softball diamonds and regulation-sized fields or to arrange for students in some sports to use city facilities.

The board is scheduled to finalize a design and get an updated cost estimate for the project in June and will ink a final “not to exceed budget” at the start of July.

Mullet madness: Young man who died in motorcycle accident remembered at local fundraiser

Mullet madness: Young man who died in motorcycle accident remembered at local fundraiser ‘Entire paradigm has to shift’: Majority of parents express support for phone ban, but predict rocky rollout

‘Entire paradigm has to shift’: Majority of parents express support for phone ban, but predict rocky rollout New Hampshire committee seeks to prevent domestic fatalities like murder-suicide in Berlin

New Hampshire committee seeks to prevent domestic fatalities like murder-suicide in Berlin ‘A little piece of everything I like’: New Pittsfield barbershop brings more than a haircut to downtown

‘A little piece of everything I like’: New Pittsfield barbershop brings more than a haircut to downtown