Rethinking Rundlett: Ahead of vote, some costs remain hidden

|

Published: 10-18-2024 5:15 PM

Modified: 10-19-2024 5:31 PM |

As any middle school math student knows, just writing the answer to a question isn’t enough. Students must show their work.

Based on estimates from its architects, the school board set a $152 million budget cap for the middle school project in July. HMFH, the architectural firm under a $10 million contract to provide designs and initial estimates for the school district, asserts that the budget includes both money for site work and infrastructure upgrades at the forested raw land at Broken Ground.

For weeks, the Monitor asked the district and HMFH for a breakdown of the $152 million project, outlining how much is expected to be spent on each portion of the new school. How much is set aside for infrastructure? How much is set aside for all the site work, like clearing the trees and building the parking lots and new roads?

They declined to provide even a range for those expenses even after repeated requests.

“I don’t have the estimate with me, I’m sorry,” an HMFH representative, laptop on the table, told the Monitor in an interview. “We can get back to you with a percentage.” In the week following that interview, that information was not provided.

The district has laid out only the broad costs of the project.

Of the $152 million budget, roughly $122 million is for construction, with another $29.6 million set aside for “soft” expenses like design and planning. It’s the most expensive school project to apply for state building aid since the Department of Education started keeping digitized records 20 years ago, even when adjusted for inflation, according to a Concord Monitor analysis.

Ample renderings, presentations and estimates are available on the website about the Middle School Project. In email exchanges, meetings, conversations, interviews and opinion pieces, board members have been earnest about why they believe Broken Ground is truly the better location.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Yet when it comes to a central assertion behind moving the school to Broken Ground — that it remains cheaper than rebuilding at Rundlett — the district and its contractors have refused to show their work.

The district has laid out additional costs for the South Street site, including millions more for demolition and an extended, five-year construction window, meaning students wouldn’t access the new school until 2030 instead of 2028.

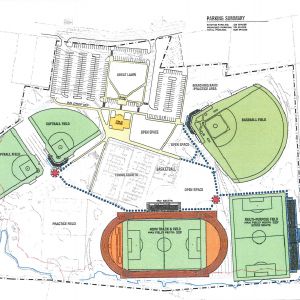

The district did provide the Monitor with a site cost comparison between the two properties. But it is based on information from November 2023, when the design at Broken Ground was projected to be built on eight acres of land, with playing fields shared with the elementary schools there. The overall footprint has since ballooned to three times that size: between 22.5 and 24.5 acres are expected to be cleared of trees, with playing fields extending out behind the school.

Cost is not the only benefit the Broken Ground site is purported to offer. But without an up-to-date breakdown, the Monitor was unable to confirm whether that promise of savings remains true.

If the board uses $16 million it has saved up for major projects and receives $30 million in state building aid — the best-case scenario for this project without major legislative action — the project would add $0.59 onto the district tax rate in the first year, according to the district.

That adds $207 to the tax bill of a $350,000 home during the first year of the bond before any increases tied to the annual school budget. If the project gets no building aid but still applies its trust fund, that number rises to $378 on the same home in the first year.

The overall cost – initially $176 million before it was scaled back – has been at the heart of conversations about a new middle school throughout the life of the project, from the reason to build new rather than renovate Rundlett and the decision not to add a fifth grade to the school.

Both before and since the Broken Ground site was selected last December, the school board and project architects have said the new location will be cheaper than if they opted to build in the South End, partially because of the money needed to demolish Rundlett.

“Right off the bat, that’s $5 million we could turn into making this Net Zero,” board member Jim Richards said in June. “It’s $5 million that we could turn into usable classrooms, facilities and things for our kids.”

That assertion was based on the November 2023 cost comparison, which was presented to the school board days before it voted to choose a new location.

Overall, that report found that the price for site costs, like demolition, at Rundlett was $5.2 million more than what it would cost for things like infrastructure and site work at the raw land near Broken Ground.

Driving the expense on South Street was the need to phase construction since students would still need to access the site during construction. The new school would have to be complete before the old Rundlett could be knocked down, and only after that could fields and other outdoor work be completed.

Because of that phasing, rebuilding at Rundlett — from shovels in the ground to all facilities being usable — would take five years, according to Keith Kelley, director of preconstruction and planning at Harvey Construction, hired by the district to plan the school. Broken Ground, by comparison, is scheduled to be completed in under three years.

“There’s absolutely a premium, both in time and money, to build on an existing site that has students, faculty, staff, sporting events, whatever else going on all around us,” Kelley said.

That extended work period carried a price tag of $3.1 million, as of last fall. Kelley said it would be higher now. It also would mean students would go without outdoor spaces for sports and recess for several years.

The estimated cost to clear trees at Broken Ground was about $1.1 million in 2023, but that figure was based on a smaller project. The school board has since decided to build three new athletic fields behind the new school and added more parking lots and roads, which calls for clearing two dozen acres of trees, not eight. The estimate for roads and parking was slightly higher at the new location, but that is similarly inaccurate because it came before the design for the area ballooned.

When it comes to infrastructure, architects estimated last year that road, water, sewer, power and other infrastructure needs at Broken Ground would be about $1.4 million more than what was needed on South Street. That number included $150,000 to relocate walking trails and $500,000 for traffic improvements, like making all sidewalks ADA compliant, putting in flashing stop signs and adding lines to South Curtisville Road.

These costs are included somewhere in the budget, but what they are under the new scope of the project is unknown.

Time is money, as they say. Reversing the planning process now would cause delays that will result in additional costs.

The school designed for Broken Ground cannot be transposed directly onto the South Street site, according to HMFH.

“You wouldn’t start from square one,” architect Tina Stanislaski said, “but the plan that we’ve developed won’t work in that location…we’d have to reconfigure everything.”

That reconfiguration would add $2.85 million in new design work, according to the district website.

In addition, any delays to the start of the project incurred while a charter amendment fight plays out, either on the board or in court — would also drive up costs. If construction expenses rise 3% each year, the low end of current trends, costs could rise by $3.6 million each year the school is delayed.

The district calculates about $10 million in new costs if the project backtracks now, on top of the cost of demolition and phased construction.

That is a hefty total. But it is incomplete: Importantly, it does not account for how much residents could stand to avoid in site work costs by not building at Broken Ground, leaving the actual price tag for reversing the vote unclear.

Beyond the cloudiness of the costs, the district has cited clear benefits to building at Broken Ground.

Kids now entering middle school were in first grade when the pandemic hit. The board doesn’t want to add more interruptions to their learning by making them go to school just a few yards from a construction zone.

“There’s been a lot of talk about, ‘it’s not a big deal,’ the kids will get through it,’” Middle School Principal Jay Richard said. “But if I had an opportunity to choose for my students, whether they had to have the construction experience on their current site or not have that experience, guess which one I’m going to pick?”

Both potential construction sites, it is worth noting, are adjacent to current schools.

Broken Ground and Mill Brook, as a unit, educate more than a third of Concord’s elementary students, including most students of that age who are learning English as a second language. The two schools are cornered by two roads — Portsmouth Street and South Curtisville Road — that would both be the main arteries for vehicles to access the new buildings’ construction site. The two dozen acres of trees that will be removed to make way for the new school include sections directly abutting the two elementary schools’ fields and playgrounds.

Rundlett is a citywide school, and disruptions would impact a broader swath of learners. Superintendent Kathleen Murphy told the Monitor that students would not be displaced from Rundlett during a build process on South Street simply because “there’s no other place to put them.” They would be far closer to an active construction zone than Broken Ground students. The same goes for elementary students at Abbott-Downing.

Both construction zones would put students’ learning environments at risk. But the period of disruption on South Street is more acute, impacts more students and takes place over a longer period of time.

One main draw of the Broken Ground site for board members was the size of the property. The district owns 59 acres, and its development extends into 29 of them. The property size gives “room to grow,” the board has said, that other district schools don’t have.

Perhaps more notably, however, the design includes some features that may not be possible on the 20-acre property off South Street.

For example, Rundlett Middle School recently installed an outdoor basketball hoop that includes four square lines painted on the blacktop. Still, it’s one of the only play areas available.

When students were asked what a new school ought to have, outdoor basketball courts was one of their top asks, architect Holly Miller said. The Broken Ground site, to execute that ask, has two of them. To fit athletic fields and a new school at Rundlett, she said, “There’s no room for a basketball court.”

When the school board sought feedback on which energy systems to include in the new design, residents were largely united in support of an investment in in-ground heat pumps. It was one of few things everyone testifying seemed to agree on – geothermal heat, carrying the greatest opportunities for rebates and being the most energy efficient, would be worth the initial investment.

Heat pumps are likely possible on South Street, Miller and Stanislaski said, but space limitations on the wells would likely require that they be supplemented by boiler heat — a hybrid system that demands more maintenance.

Looking toward the future, some residents have wondered why, if district enrollments are continuing to decline, the 900-student middle school would need “room to grow.”

“Down the road, maybe we’ll need to put some preschools into our elementary— that moves that fifth grade out, and it could become a five through eight” middle school, Murphy said. “The building is set up so that we could do that. We couldn’t do that at Rundlett.”

Of all the board’s reasons to move the school to East Concord — from the benefits of a larger property to the educational and financial detriment of building alongside a school that remains in use — many of them are well supported.

It’s possible that cost falls in that camp: sizable added expenses to building on South Street are evident. Without knowing the current site development and infrastructure earmarks, residents have been left to trust that the math that the expenses at South Street still surpass those unique to Broken Ground, even as the design changes.

With a Nov. 5 vote on two charter amendments targeting the board’s decision to relocate the middle school, many residents, like Debra Samaha, can’t accept that.

“You still have not provided major infrastructure costs. You say they’re built into the budget: we can’t see them, we have asked repeatedly what they are, point blank. We cannot get answers from you,” Samaha said to the board when it set the budget cap in July. “As taxpayers, we need to know the true cost.”

Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project

Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project  Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now?

Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now? Concord businesses receive grants to build self-sufficiency

Concord businesses receive grants to build self-sufficiency A soggy spring continues

A soggy spring continues