Opinion: The tragic and forgotten story of Viola Liuzzo

Jonathan P. Baird photo Jonathan P. Baird photo

| Published: 11-04-2024 6:00 AM |

Jonathan P. Baird lives in Wilmot.

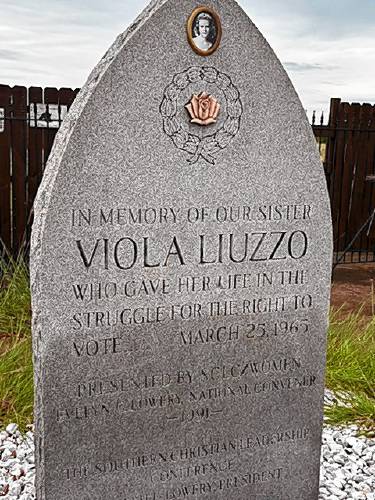

On US Highway 80, in the middle of a 54-mile stretch between Selma and Montgomery, there is a small unmarked memorial on the hillside near the road. It is a rectangular, fenced-in space dedicated to the memory of civil rights activist, Viola Liuzzo. The location is near the spot where Liuzzo died.

I have now seen it twice and there is an aura of loneliness about this very deserted stop. No Alabama highway signs announce the destination. Driving by, it can be easily missed.

Viola Liuzzo was the only white woman killed down south during the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Her story has largely been forgotten but she was a true hero who demonstrated courage and dedication to social justice. Both times I have viewed the marker, I left feeling the gravity of her actions. She stepped up bravely in a most dangerous situation. It is wrong that she has not been recognized and honored by Alabama and the nation.

Like millions of others, Liuzzo watched the events of Bloody Sunday unfold on TV. It was March 7, 1965. The nation was transfixed watching 600 civil rights marchers led by 25-year-old John Lewis get brutally beaten by Alabama state troopers.

For months, efforts in Selma to register Black voters had been stalled. Just 156 of Selma’s 15,000 Black people of voting age were on the voting rolls. Tensions had increased dramatically after Alabama state troopers murdered Jimmy Lee Jackson in the nearby town of Marion in February.

After the police violence prevented the Bloody Sunday march, Dr. King asked people who believe in justice to come to Selma. 25,000 people responded, including Liuzzo, who was inspired to make the trek. She had cried watching Bloody Sunday. She tried to get others to accompany her without success. She drove alone from her home in Detroit to Selma.

Liuzzo’s husband, Jim Liuzzo, was not happy his wife was going to Alabama but he could not dissuade her. The Liuzzos had five children. They both knew it was dangerous. Viola knew the South well. As a younger person she had lived in Jim Crow Georgia and Tennessee but was determined to go.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Restaurant owner settles lawsuit against Franklin, but didn’t get what she sought

Restaurant owner settles lawsuit against Franklin, but didn’t get what she sought

Trump’s order to end homelessness could overwhelm New Hampshire’s mental health system, advocates say

Trump’s order to end homelessness could overwhelm New Hampshire’s mental health system, advocates say

With Steeplegate still held up in court, city privately debates public investment

With Steeplegate still held up in court, city privately debates public investment

Former Castro’s building to hold apartments and the cigar shop will return, eventually

Former Castro’s building to hold apartments and the cigar shop will return, eventually

‘Peace of mind’: As New Hampshire nixes car inspections, some Concord residents still plan to get them

‘Peace of mind’: As New Hampshire nixes car inspections, some Concord residents still plan to get them

Education commissioner nominee Caitlin Davis receives unanimous bipartisan support on eve of confirmation vote

Education commissioner nominee Caitlin Davis receives unanimous bipartisan support on eve of confirmation vote

After that first attempted march on Bloody Sunday, activists obtained a court order that permitted a new protest and march. It occurred March 21-25, 1965. During her time in Selma, Liuzzo marched the first day. Then she worked at a hospitality desk welcoming and registering volunteers. Later she worked at a first aid station. She allowed her car to be used to ferry marchers to locations they needed to go.

After the march, she was planning to go home the next day. She spent her last day driving people back and forth between Selma and Montgomery. She and a 19-year-old black man, Leroy Moton, were on their last run back to Montgomery when they were followed by a car full of Klansmen.

It is possible the Klansmen noticed her Michigan plates and it is also possible they saw a Black man and a white woman in the car together. Southern white people of that era hated outside agitators (especially from the North) and race-mixing. Whether what happened was spontaneous or planned remains a subject of controversy.

To this day, the details of the attack are disputed but the prevailing story was that after a high speed chase, Liuzzo, who was the driver, was shot and murdered by one of the Klan members who shot from a car racing alongside. Liuzzo’s car went off the road, crashing into a fence. Moton survived but Liuzzo died instantly from the gunshots to her head.

The case was quickly solved because among the four Klansmen in the car was an undercover FBI informant, Gary Tommy Rowe. Rowe reported to the FBI about the events of the evening. He had a reputation for violence both because he boasted about it and also because he had previously beaten Freedom Riders. The other Klansmen in the car fingered Rowe as the trigger man. Many questions arose about Rowe’s conduct and why he had not acted to save Liuzzo.

The FBI and its director, J. Edgar Hoover, played a despicable role in these events. Hoover opposed the civil rights movement as a threat to civil order. In an effort to deflect attention from the FBI’s negligence, Hoover conducted a smear campaign against Liuzzo. I believe it was this smear campaign, similar to what they conducted against Dr. King, that erased Liuzzo from our history.

The smear campaign was vicious. Hoover leaked rumors to the press that Liuzzo was a drug addict, that she was having an affair with Leroy Moton, that she was emotionally unstable and that she had abandoned her children. Hoover scapegoated Liuzzo to hide the FBI’s disgraceful role, especially the fact a key FBI informant was in the car with the Klansmen.

The Liuzzo family suffered greatly. Local Detroit racists burnt a cross on their lawn, fired bullets into their home, and dumped garbage on their lawn. The Liuzzo children were called “n—er lovers” and actually had rocks thrown at them on their way to school. Hate mail and obscene phone calls were relentless. It got so bad Jim Liuzzo had to hire an armed security guard to protect his home. The emotional stress on the family was enormous.

After a hung jury in the first state court murder trial, the Klansmen charged in Liuzzo’s murder were acquitted by an all-white male jury. The racism in those proceedings was off the charts. In open court, Matt Murphy, lead defense counsel for the Klansmen, called Liuzzo “a white n—er who turned her car over to a black n—er for the purpose of hauling n—ers and communists back and forth.” That vignette captures the flavor of the trial.

The Klansmen in the car, with the exception of Rowe, were later convicted in federal court on the charge of conspiracy to violate Liuzzo’s civil rights. They received 10-year sentences. Rowe was also subsequently indicted for murder but that case failed. The court said Rowe had immunity from prosecution because of a deal he made for testifying against the other Klansmen.

In 1983, 18 years after her murder, in a civil case in federal court, the Liuzzo family sued the FBI for its responsibility in Viola’s death. The Court rejected the Liuzzos’ suit, unbelievably saying that the plaintiffs failed to show the FBI had been negligent in directing their agent. To add insult to injury, the Court ordered the Liuzzos to pay the government’s court costs of $80,000. After the TV show 20/20 aired a segment, the Justice Department dropped the court cost claim.

The Liuzzo marker on US Highway 80 has been repeatedly desecrated and defaced. In 1997, vandals painted a large Confederate flag across the face of the stone. This seems symbolic of the ugly effort to slander and discredit Viola Liuzzo. She deserves so much better. She died at age 39. She stands in the best tradition of Americans who selflessly fought white supremacy, racism, and segregation.

Her death added much impetus to President Johnson’s effort to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Maybe someday America will have a different take on who its real heroes are.

Opinion: Trumpism in a dying democracy

Opinion: Trumpism in a dying democracy Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today Opinion: The art of diplomacy

Opinion: The art of diplomacy Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community

Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community