Latest News

One dead in Lantern Lane fire in Concord

One dead in Lantern Lane fire in Concord

Mold found in Bow Community Building

Mold found in Bow Community Building

With new plan for multi-language learners, Concord School District shifts support for New American students

Every time Leanna Kenza laces up her sneakers and steps on the track, it gives her reprieve from the day-to-day drama of eighth grade and the chance to find a new friend.While most Rundlett Middle School parents were enrolling their kids in sports in...

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

With Concord reduced to a single movie theater for the first time in living memory and New Hampshire chain Chunky’s Cinema Pub closing two of its three locations, going out to the flicks in the Granite State just keeps getting harder.Don’t expect that...

Most Read

No deal. Laconia buyer misses deadline, state is out $21.5 million.

No deal. Laconia buyer misses deadline, state is out $21.5 million.

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

“It’s beautiful” – Eight people experiencing homelessness to move into Pleasant Street apartments

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

With Concord down to one movie theater, is there a future to cinema-going?

Quickly extinguished fire leaves Concord man in critical condition

Quickly extinguished fire leaves Concord man in critical condition

Concord police ask for help in identifying person of interest in incidents of cars being keyed during Republican Party event

Concord police ask for help in identifying person of interest in incidents of cars being keyed during Republican Party event

Editors Picks

What’s in a name? Ask an Epsom Yeaton.

What’s in a name? Ask an Epsom Yeaton.

Downtown cobbler breathes life into tired shoes, the environmentally friendly way

Downtown cobbler breathes life into tired shoes, the environmentally friendly way

People of color incarcerated at higher rates in New Hampshire, but data is limited

People of color incarcerated at higher rates in New Hampshire, but data is limited

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

Former Concord firefighter sues city, claiming years of homophobic sexual harassment, retaliation

Sports

High schools: Concord girls’ lax picks up first win, Tide softball handed first loss in pitchers’ duel

Girls’ LacrosseConcord 20, Nashua North 7Key players: Concord – Emma Pelletier (8 goals, 5 draw controls), Sofia Payne (6 goals, 2 assist), Sarah Leuci (3 goals, 10 draw controls), Sydney Brown (goal, assist), Ava Philbrook (goal, assist), Malie...

Patriots’ draft approach likely to be different in post-Belichick era

Patriots’ draft approach likely to be different in post-Belichick era

High schools: Weekend results

High schools: Weekend results

Opinion

Opinion: The truth of it

John Buttrick writes from his Vermont Folk Rocker in his Concord home, Minds Crossing. He can be reached at johndbuttrick@gmail.com Watching and reading the news today involves frequent exposure to the word “existential,” employed to mean truth....

Opinion: A bad idea for New Hampshire

Opinion: A bad idea for New Hampshire

Opinion: Medical Aid in Dying would have spared my father’s suffering

Opinion: Medical Aid in Dying would have spared my father’s suffering

Opinion: NH youth’s effort for a more robust climate curriculum

Opinion: NH youth’s effort for a more robust climate curriculum

Opinion: Inherited hatred and how to stop it

Opinion: Inherited hatred and how to stop it

Politics

Charities will not have to pay rent to casinos under new law

Deb Leahy can finally breathe easy, freed from the fluctuating rental fees each time her organization partners with a New Hampshire casino for donations.Thanks to a new law, casinos are now prohibited from imposing rent charges on charities for...

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

Sununu says he’ll support Trump even if he’s convicted

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

NH mayors want more help from state on homelessness prevention funds

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

Two democrats with parallel views run for same State Senate seat

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

House passes bill removing exceptions to state voter ID law

Arts & Life

Celebrate agriculture, education, and community at the NH Farm, Forest, and Garden Expo

Deerfield, NH — The New Hampshire Farm, Forest, and Garden Expo returns this spring, promising an exciting blend of agriculture, education, and family fun.Scheduledfor Friday, May 3, 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. and Saturday, May 4, and 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., the Expo...

Active Aging: John Burke of Peterborough celebrated his 81st birthday with 81 hikes up Pack Monadnock

Active Aging: John Burke of Peterborough celebrated his 81st birthday with 81 hikes up Pack Monadnock

Vintage Views: From darkness to light

Vintage Views: From darkness to light

Obituaries

Joanna M. Cloe

Joanna M. Cloe

formerly of Pembroke, NH - Joanna Mary (Cavanagh) Cloe, 79, passed away in Florida April 17th after a short illness. She was formerly a longtime resident of Pembroke, NH and member of St. John the Baptist Church. She was born in Bat... remainder of obit for Joanna M. Cloe

Rita A. French

Rita A. French

Contoocook, NH - Rita A. French, age 98, of Park Ave, passed away peacefully on Monday, April 22, 2024 at her home. She was born in Barton, VT one of 7 Children to the late Samuel and Myra (Leonard) Paul. Rita worked at Concord Hos... remainder of obit for Rita A. French

Elizabeth G. Mahon

Elizabeth G. Mahon

Elizabeth "Betty" G. Mahon Boscawen, NH - Elizabeth "Betty" G. Mahon, age 93, passed away peacefully on Saturday, April 13, 2024 with family by her side. She was born in Salem, MA daughter of the late John and Elizabeth (Tansey) Gannon.... remainder of obit for Elizabeth G. Mahon

Marylee Meagher

Marylee Meagher

Hudson, NH - Marylee Meagher, 67, of Hudson, passed away Friday, April 19, 2024 at Southern NH Medical Center surrounded by her family and friends. She was born on October 15, 1956 in Nashua, daughter of the late Edgar and Agnes (Le... remainder of obit for Marylee Meagher

Getaway driver in Winnipesaukee hit-and-run arrested

Getaway driver in Winnipesaukee hit-and-run arrested

Head of NH Port Authority placed on administrative leave

Head of NH Port Authority placed on administrative leave

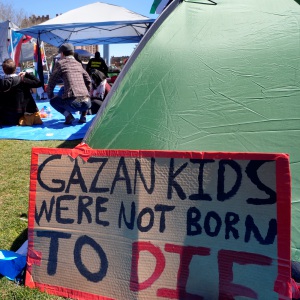

As UNH hosts rally against Gaza war, lawmakers weigh campus free speech protections

As UNH hosts rally against Gaza war, lawmakers weigh campus free speech protections

Opinion: Public school standards overhaul will impact every facet of public education in NH

Opinion: Public school standards overhaul will impact every facet of public education in NH

High schools: Bow track sweeps 4-team meet at Pembroke

High schools: Bow track sweeps 4-team meet at Pembroke

Christa McAuliffe sabbatical recipient plans to launch students into space through escape room-inspired game

Christa McAuliffe sabbatical recipient plans to launch students into space through escape room-inspired game

High schools: Coe-Brown softball wins 5th straight, Concord’s McDonald pitches first varsity win, Tide’s Doherty scores 100th career point

High schools: Coe-Brown softball wins 5th straight, Concord’s McDonald pitches first varsity win, Tide’s Doherty scores 100th career point High schools: Bow’s Kelly lifts Falcon softball to victory in walk-off, more Monday results, plus Saturday’s track meets

High schools: Bow’s Kelly lifts Falcon softball to victory in walk-off, more Monday results, plus Saturday’s track meets Community Players of Concord present newest adaptation of Pride and Prejudice

Community Players of Concord present newest adaptation of Pride and Prejudice Concord Monitor editor Mike Pride’s final book explores the lives, works of Northern New England poets

Concord Monitor editor Mike Pride’s final book explores the lives, works of Northern New England poets