Latest News

Charlestown plane crash injures one

Charlestown plane crash injures one

Concert on the lawn coming to Pierce Manse

Concert on the lawn coming to Pierce Manse

Concord belly dancing class teaches self love and connectedness: ‘I am enough’

At the beginning of her belly dancing class, Dawn Higgins asks her participants to recite two mantras: “I am beautiful” and “I am enough.”

Cannon Mountain tram to shut for at least two years while replacement is installed

If you’ve always wanted to ride the aerial tram to the top of Cannon Mountain, you’d better hurry up.

Most Read

Editors Picks

A Webster property was sold for unpaid taxes in 2021. Now, the former owner wants his money back

A Webster property was sold for unpaid taxes in 2021. Now, the former owner wants his money back

Report to Readers: Your support helps us produce impactful reporting

Report to Readers: Your support helps us produce impactful reporting

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

Productive or poisonous? Yearslong clubhouse fight ends with council approval

Productive or poisonous? Yearslong clubhouse fight ends with council approval

Sports

Concord National LL Softball wins State Championship and moves on to Little League Regional Tournament

The Concord National Youth Softball 12U All-Stars team booked a trip down to Bristol, Conn., to represent New Hampshire in the Little League New England Region Tournament for the second year in a row with a win over Mount Monadnock on Saturday, 13-3.

Josiah Hakala of Beaver Meadow wins State Amateur golf championship

Josiah Hakala of Beaver Meadow wins State Amateur golf championship

Athlete of the Week: Grace Saysaw, Concord High School

Athlete of the Week: Grace Saysaw, Concord High School

Local golfers tee off at 122nd Amateur Championship

Local golfers tee off at 122nd Amateur Championship

Opinion

Opinion: Trumpism in a dying democracy

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today

Opinion: The art of diplomacy

Opinion: The art of diplomacy

Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community

Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community

Opinion: Iran and Gaza: A U.S. foreign policy of barbarism

Opinion: Iran and Gaza: A U.S. foreign policy of barbarism

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Politics

New Hampshire school phone ban could be among strictest in the country

When Gov. Kelly Ayotte called on the state legislature to pass a school phone ban in January, the pivotal question wasn’t whether the widely popular policy would pass but how far it would go.

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Arts & Life

Artist Spotlight: Holly Emrick

This week’s artist spotlight, brought to you through a collaboration with the Concord Insider and the Concord Arts Market, focuses on Holly Emrick, who lives in Boscawen. A 58-year-old mother of two and grandmother of two and a wife of 40 years, Emrick discovered jewelry-making during her 16 years as a stay-at-home mom.

Nate Lavallee, July Young Professional of the Month: Stretching toward strength, self-care and Southern NH wellness

Nate Lavallee, July Young Professional of the Month: Stretching toward strength, self-care and Southern NH wellness

Lavender haze: Purple fields bloom at Warner farm

Lavender haze: Purple fields bloom at Warner farm

Arts in the Park returns for July

Arts in the Park returns for July

Hopkinton art gallery showcases “Creativity Beyond Convention”

Hopkinton art gallery showcases “Creativity Beyond Convention”

Obituaries

Sharon Parmenter

Sharon Parmenter

Boscawen , NH - Sharon A. Parmenter, 78, of Boscawen, passed away with family and friends by her bedside on the evening of July 2, 2025 at Concord Hospital. Sharon was born in Plymouth, NH on December 19, 1946, the first daughter to... remainder of obit for Sharon Parmenter

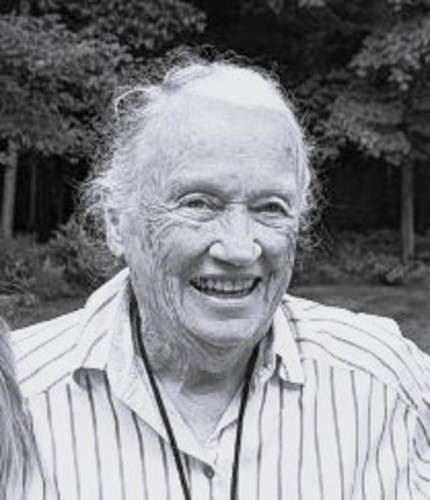

Elizabeth Terrell

Elizabeth Terrell

Concord, NH - Elizabeth "Liz" Terrell passed away on July 12, 2025, at Pine Rock Manor after several months of declining health. She was two months shy of turning 91 years old. She was born on September 15, 1934, in New Rochelle, New Yo... remainder of obit for Elizabeth Terrell

Arnold Stetson

Arnold Stetson

Arnold "Stet" Stetson Elkins, NH - Arnold "Stet" E. Stetson, 90, of Wilmot Center Road, died Sunday, July 13, 2025 at his home. He was born in East Andover, NH on December 30, 1934 the son of Richard F. and Martha (Crewe) Stetson. H... remainder of obit for Arnold Stetson

John W. Herbert

John W. Herbert

Salisbury, NH - John W. Herbert, a proud Navy veteran, devoted family man, and longtime member of the Salisbury community, passed away peacefully on June 28, 2025, at the age of 82. Born and raised in City Island in the Bronx, New York... remainder of obit for John W. Herbert

Ayotte vetoes bathroom bill, defeating it for second time in two years

Ayotte vetoes bathroom bill, defeating it for second time in two years

Ayotte vetoes ‘book ban’ bill, splitting with Republicans

Ayotte vetoes ‘book ban’ bill, splitting with Republicans

Concord city council divided over raise for city manager to nearly $250K

Concord city council divided over raise for city manager to nearly $250K

‘The football experience’: Youth flag football kicks off in Concord with new co-ed summer league

‘The football experience’: Youth flag football kicks off in Concord with new co-ed summer league

NH judiciary launches review of domestic violence case that led to murder of Berlin woman

NH judiciary launches review of domestic violence case that led to murder of Berlin woman

Free speech group, residents back Bow parents’ free speech appeal in case involving transgender athletes

Free speech group, residents back Bow parents’ free speech appeal in case involving transgender athletes

Youngsters Richardson and Hakala move on, and veterans crash out at 122nd State Amateur Championship

Youngsters Richardson and Hakala move on, and veterans crash out at 122nd State Amateur Championship Concord became a Housing Champion. Now, state lawmakers could eliminate the funding.

Concord became a Housing Champion. Now, state lawmakers could eliminate the funding. ‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference

‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference  Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide