Opinion: High brows versus low brows

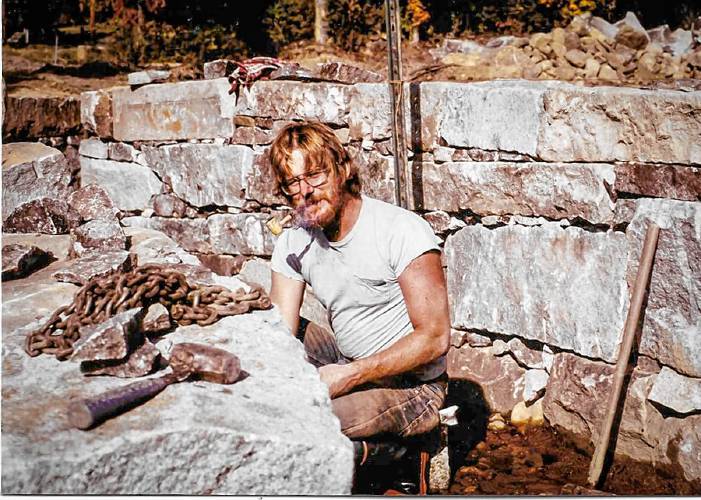

“Then a miracle happened. Sometime in my thirties, perhaps out of exhaustion, it came to me I didn’t need to choose sides. I could honor both. Jean Stimmell photo

| Published: 11-03-2024 6:00 AM |

Jean Stimmell, retired stone mason and psychotherapist, lives in Northwood and blogs at jeanstimmell.blogspot.com.

Even if Kamala wins on Tuesday, NYT Columnist Bret Stephens asks two provocative questions: “How did Trump still get so very, very close? And how can we fashion a liberalism that doesn’t turn so many ordinary people off?”

While science and rationality have brought much progress, they have also made modern life remote and bureaucratic, leaving many feeling abandoned and cast adrift in a sea of unfathomable numbers. Worse yet, income inequality has reached levels not seen since the Gilded Age, leaving working Americans struggling to stay afloat.

Let’s face it: Modernity is a cold fish. Folks no longer feel truly seen and appreciated, as they did in the past when they were a seamless part of a close-knit community wrapped in tradition within the timeless rhythms of nature.

I’ve been meditating on this topic ever since coming across the esoteric theories of Owen Barfield, someone I had never heard of until this week. He was an original thinker, born in 1898, who influenced, among others, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, Saul Bellow, and Marshall McLuhan.

According to Barfield, today’s cultural elite is blinded by “chronological snobbery” because they are “incapable of thinking that something can be, at the same time, both concrete and abstract.”

That wasn’t always the case. In fact, quite the opposite: it is we today, not older traditional societies, who have lost the ability to experience the world “in a manner that unites physical and spiritual, material and immaterial.”

Barfield points out how “ever since Christianity became institutionalized in the fourth century, man has increasingly cut himself off from the universe around him. Whereas people once experienced ideas and nature in a direct, unmediated way, they now view nature scientifically as a dead object cut off from their own individual, subjective identity.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

New Hampshire providers brace for Medicaid changes that reach beyond healthcare

New Hampshire providers brace for Medicaid changes that reach beyond healthcare

New England College expands $10,000-per-year offer to Concord, Bishop Brady graduates

New England College expands $10,000-per-year offer to Concord, Bishop Brady graduates

Concord school leaders weigh the future of middle school project without state building aid

Concord school leaders weigh the future of middle school project without state building aid

Truck collision on South Main Street in Concord diverts traffic

Truck collision on South Main Street in Concord diverts traffic

Warner shot down a housing developer’s bid. New statewide zoning mandates could clear a path for proposals like it.

Warner shot down a housing developer’s bid. New statewide zoning mandates could clear a path for proposals like it.

That’s a major reason why working folks, who tend to live a more traditional lifestyle, feel betrayed by the highly educated elite who champion abstractions and new-fangled theory over actual, lived experience.

Progressive elites also advocate for sweeping changes in existing societal norms, which, no matter how laudable in the abstract, move too fast for slow-moving traditional mores to catch up — especially when these changes are thrown into the maelstrom of today’s culture wars.

I’ve experienced both sides of these culture wars. I have been infatuated with bookish theories about why things happen since falling in love with Plato at age 10. But I had another wild and crazy side, intent on living fully in the moment, reveling in manual labor by day and carousing at night.

Until I was in my thirties, I tried to do both: Attending St. Pauls, Columbia, UNH, and Antioch, interspersed with literally scores of blue-collar jobs from factory worker to union construction to gunnery fire control in Vietnam.

My abstract side and practical side were at war with each other. For years, I drove myself crazy, attempting to choose a side, as in this example I wrote when I was a stone mason:

“Driving to work as the sun was coming up, chugging down thermoses of coffee, agonizing over esoteric theories. By the time I got to the job site, I had tied my mind in a knot. But then magic happened: With fingers tingling from the cold, picking up that first gnarly rock from the pile and carrying it gingerly through slippery mud to the place in the wall where I knew it should go; at that moment, I became whole again. My mind stopped: It was just me, the rock, and my frosty breath on a sparkling autumn morning.”

Then a miracle happened. Sometime in my thirties, perhaps out of exhaustion, it came to me I didn’t need to choose sides. I could honor both.

As Barfield understood, I can honor the act of fitting a particular rock where it belongs in a stone wall while equally honoring the abstract joy of fitting facts together to build a theory about how we can better live together.

It is not either/or but both/and. That’s the answer to Bret Stephen’s question about how can we fashion a liberalism that “doesn’t turn so many ordinary people off.”

To flourish, we must value the important contributions of both sides of our current cultural divide. As Americans, we are all brothers and sisters in a common cause. Let’s not let a demagogue divide and conquer us.

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today Opinion: The art of diplomacy

Opinion: The art of diplomacy Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community

Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community Opinion: Iran and Gaza: A U.S. foreign policy of barbarism

Opinion: Iran and Gaza: A U.S. foreign policy of barbarism