As algae blooms in lakes get more common, spotting them by drone makes sense

Researcher Christine Bunyon collects a cyanobacteria sample from Keyser Pond in Henniker in 2022. Christine Bunyon / UNH—Courtesy

| Published: 10-16-2023 10:32 AM |

As more New Hampshire lakes suffer from blooms of toxic algae due to warming weather and increased development, two water bodies in Henniker were part of a study of a faster way to spot outbreaks, using drones.

“With the (drone), a small lake might take as little as 10 to 15 minutes to fly over and less than an hour to do everything including set up, flying and packing away the equipment – and an entire lake’s worth of imagery could be processed within just two hours,” Christine Bunyon, a UNH graduate student researcher and lead author of the study, said in a UNH press release. “The traditional method of testing for cyanobacteria took so much longer because each sample had to be collected and processed individually.”

Co-authors include Russell Congalton, professor of natural resources and the environment and a scientist at the N.H. Agricultural Experiment Station; Amanda McQuaid, UNH Extension specialist; and Benjamin Fraser, a postdoctoral researcher.

The work comes as New Hampshire had the highest number of cyanobacteria blooms ever reported, according to data from the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services.

The blooms usually result from nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus washing into a lake after a rainstorm or entering from leaking septic systems. The extra food causes a population explosion among bacteria that are already there, creating the slimy, often smelly blooms.

Usually, the blooms use up all the oxygen in the water to the point that the bacteria suffocate and die, which makes them release toxins that poison life around them.

This scenario becomes more possible in warmer water, which is why climate change is helping fuel the increase.

The study, published in the Journal of Remote Sensing, detailed using a UAS (unmanned aircraft system, the official term for drones) equipped with a multispectral sensor to capture imagery in various wavelengths of the spectrum – blue, green red, red edge, and near-infrared – that allowed detection of blue-green and green algae.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

They flew the drone over six bodies of water in southern New Hampshire, including Keyser and French ponds in Henniker. The drone collected images of the lake in a lateral grid pattern to analyze and determine cyanobacteria concentrations. Water samples were also collected by a researcher and analyzed to determine the accuracy of the results of the image analysis.

The team conducted their water surveys from May 2022 to September 2022. The lakes that were studied were chosen based on various factors, including previous bloom duration, concentrations, and dominant cyanobacteria species, lake size, public accessibility, and distance from water quality and image analysis laboratories.

The study also revealed a correlation between cyanobacteria cell concentration and concentrations of chlorophyll-a and phycocyanin, the pigment responsible for the blue-green algae’s color. This correlation allowed for the use of spectral imagery to identify concentrations of cyanobacteria, chlorophyll-a and phycocyanin in the water, helping determine potential harm levels.

Co-authors include Amanda McQuaid, UNH Extension specialist, and Benjamin Fraser, a postdoctoral researcher.

The research was funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the N.H. Agricultural Experiment Station and the state of New Hampshire.

Material reported by UNH News was used in this report.

Memorial Day events in the Concord area

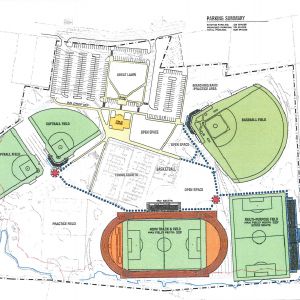

Memorial Day events in the Concord area Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project

Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project  Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now?

Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now? Concord businesses receive grants to build self-sufficiency

Concord businesses receive grants to build self-sufficiency