‘Would you raise your right hand?’ — Local veterans consider the meaning of Memorial Day

When Mason DeFrancesco initially returned home to Concord from four years of service in the Marines, he spent his first few Memorial Days going to the New Hampshire State Cemetery in Boscawen and thinking of those he knew who didn’t return home.

‘The smiles say it all’: Sweet Dreamz brings creative soft-serve to Penacook

At Sweet Dreamz in Penacook, hardware, animals and ice cream mix every day.

Most Read

By all appearances, Canadians are leery of coming to NH

By all appearances, Canadians are leery of coming to NH

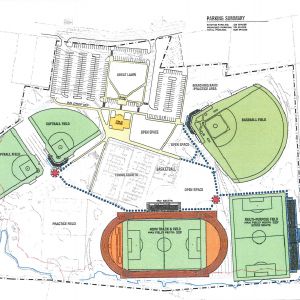

Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project

Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project

“A dream come true” – Family opens housing for adults with disabilities in Concord

“A dream come true” – Family opens housing for adults with disabilities in Concord

Memorial Day events in the Concord area

Memorial Day events in the Concord area

Giving life back to board sports: Back Alley Boards upcycles boards into art

Giving life back to board sports: Back Alley Boards upcycles boards into art

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

Editors Picks

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

‘We honor your death’ – Arranging services for those who die while homeless in Concord

‘We honor your death’ – Arranging services for those who die while homeless in Concord

Sports

Girls’ lacrosse: Bow bounces back with 13-3 win over Bishop Brady

Bow needed to bounce back after their five-game win streak was cut short but John Stark on Monday. Josie Johnson swooped in with a first-half hat-trick alongside a strong Falcons front line to win easily at home and keep moving toward the playoffs.

Opinion

Opinion: Unfair taxes, unfair schools: The New Hampshire way

Ted Morgan is a retired professor of political science living in Tamworth.

Opinion: In the fight to stop sexual violence, can polio hold the solutions?

Opinion: In the fight to stop sexual violence, can polio hold the solutions?

Opinion: Where are the permanent solutions for a more stable budget?

Opinion: Where are the permanent solutions for a more stable budget?

Opinion: My memories of Vietnam 50 years later

Opinion: My memories of Vietnam 50 years later

Opinion: Concord officials: Can we sit and talk?

Opinion: Concord officials: Can we sit and talk?

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Politics

Concord became a Housing Champion. Now, state lawmakers could eliminate the funding.

In December, Concord’s work to clear the path for more housing hit a new level.

Arts & Life

Young Professional of the Month Katie Duncan shares about creativity, community, connection

Meet Katie Duncan, Membership Manager and Educational Outreach Coordinator at the Capitol Center for the Arts. The 35-year old Concord resident’s passion for the arts and the Concord community shines through her work. From theater stages to local lakes, Katie shares how growing up in Greater Concord shaped her path—and why she’s dedicated to giving back.

Tiny Tapestry sale at Red River Theaters raising money for Concord Coalition to End Homelessness

Tiny Tapestry sale at Red River Theaters raising money for Concord Coalition to End Homelessness

Bowling for a cause: Angelman Syndrome Fundraiser coming to Boutwell’s

Bowling for a cause: Angelman Syndrome Fundraiser coming to Boutwell’s

Beautify Allenstown hosting community cleanup day

Beautify Allenstown hosting community cleanup day

Donating “The Bibliophile”

Donating “The Bibliophile”

Obituaries

Doris M. McCormack

Doris M. McCormack

Doris M. "Dot" McCormack Barnstead, NH - Doris M. "Dot" McCormack, 81, of Barnstead, NH, passed away peacefully on May 16, 2025, after a brief illness. She was born on April 9, 1944, in New Bedford, MA, daughter of the late Lucien and L... remainder of obit for Doris M. McCormack

Cynthia Atwell

Cynthia Atwell

Cynthia "Cindi" Atwell Barnstead, NH - Cynthia "Cindi" Atwell, 73, of Barnstead, NH, passed away peacefully on May 13, 2025, surrounded by her loving family after a long and courageous battle with dementia and cancer. Born on December 1... remainder of obit for Cynthia Atwell

Roger Lincoln Sullivan

Roger Lincoln Sullivan

New London, NH - Roger Lincoln Sullivan, 85, of Clover Lane, died Sunday, May 18, 2025 at his home. He was born in Bridgeport, CT on February 12, 1940 the son of Albert L. and Edith (Riley) Sullivan. Roger was raised in Stratford, ... remainder of obit for Roger Lincoln Sullivan

James Richard Mikesell

James Richard Mikesell

James "Jim" Richard Mikesell Concord, NH - James Richard Mikesell, 82, a resident of Concord, NH, passed away on May 9, 2025, surrounded by his loving family. He was born on May 30, 1942, to his late parents, Reuben Byron and Mary Ellen ... remainder of obit for James Richard Mikesell

New Hampshire school phone ban could be among strictest in the country

New Hampshire school phone ban could be among strictest in the country

Opinion: Beaver Meadow could be managed better. The new proposal might work.

Opinion: Beaver Meadow could be managed better. The new proposal might work.

Gardening season is here (if it will ever stop raining!)

Gardening season is here (if it will ever stop raining!)

Vintage Views: The Great Cattle Roundup of 1947

Vintage Views: The Great Cattle Roundup of 1947

Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now?

Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now?

Concord businesses receive grants to build self-sufficiency

Concord businesses receive grants to build self-sufficiency

Artist Spotlight: Brittany Batchelder

Artist Spotlight: Brittany Batchelder

N.E. will have enough electricity this summer but future winters may start to get dicey

N.E. will have enough electricity this summer but future winters may start to get dicey

High schools: John Stark’s Philibotte pitches shutout, hits game-winning RBI in 1-0 win, plus more results from Wednesday

High schools: John Stark’s Philibotte pitches shutout, hits game-winning RBI in 1-0 win, plus more results from Wednesday High schools: Freitas 1-hitter leads Hopkinton softball to shutout; Tuesday’s baseball, lax, tennis and track results

High schools: Freitas 1-hitter leads Hopkinton softball to shutout; Tuesday’s baseball, lax, tennis and track results High schools: Belmont’s Divers pitches perfect game; Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results

High schools: Belmont’s Divers pitches perfect game; Monday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse and tennis results High schools: Pelletier scores 100th goal, leads Concord girls’ lax to first win; baseball, softball, boys’ lacrosse and track results from this weekend

High schools: Pelletier scores 100th goal, leads Concord girls’ lax to first win; baseball, softball, boys’ lacrosse and track results from this weekend ‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference

‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference  Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week

Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week