A Webster property was sold for unpaid taxes in 2021. Now, the former owner wants his money back

Michael Durgin knew he couldn’t afford the three-bedroom house with gray siding in Webster that he’d inherited.

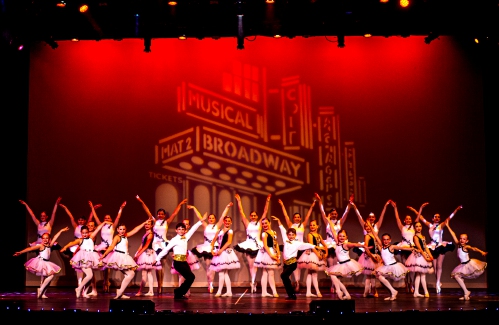

Photos: Concord High students strut their stuff at prom

With dresses, ties, sunglasses, and shoes of all colors, Concord High students rocked the red carpet at prom on Thursday evening. Smiles beamed bright and sparkles shone in the sunlight as people gathered with their dates and their friends to celebrate the conclusion of four years of hard work. Take a look at some of these stylish seniors with these red carpet highlights!

Most Read

State Supreme Court says towns can keep excess school taxes rather than sharing them with poorer towns

State Supreme Court says towns can keep excess school taxes rather than sharing them with poorer towns

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

Both remaining Rite Aid stores in Concord slated for closure

Both remaining Rite Aid stores in Concord slated for closure

New fair coming next week to Everett Arena in Concord

New fair coming next week to Everett Arena in Concord

Universal EFA program sees 500 applications in day one of expansion

Universal EFA program sees 500 applications in day one of expansion

Big projects, both noticed and ignored, marked Chip Chesley’s long career in Concord

Big projects, both noticed and ignored, marked Chip Chesley’s long career in Concord

Editors Picks

Missing in Manchester: A timeline of the missing persons investigation for Glenn Chrzan

Missing in Manchester: A timeline of the missing persons investigation for Glenn Chrzan

Inside EFAs: How school vouchers have fueled a Christian school enrollment boom in New Hampshire

Inside EFAs: How school vouchers have fueled a Christian school enrollment boom in New Hampshire

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

Productive or poisonous? Yearslong clubhouse fight ends with council approval

Productive or poisonous? Yearslong clubhouse fight ends with council approval

Sports

Softball: Coe-Brown stays ahead of MV and advances to championship with 18-9 win

The Coe-Brown softball team trusted its bats from beginning to end to outscore Merrimack Valley in the Division II semifinals on Wednesday. An eight-run first inning and a seven-run sixth saw the Bears run away and move on to the state finals.

Softball: Concord’s underdog run ends in semis to undefeated Lancers, 2-1

Softball: Concord’s underdog run ends in semis to undefeated Lancers, 2-1

Opinion

Opinion: Friends don’t let friends drive drunk

Benjamin Netanyahu and I agree on virtually nothing. But a statement he made three days after the massacre of 1,200 Israelis by Hamas in October 2023 rings true:

Opinion: Concord should be run like a household, not a business

Opinion: Concord should be run like a household, not a business

Opinion: How dark can it get?

Opinion: How dark can it get?

Opinion: Unfair taxes, unfair schools: The New Hampshire way

Opinion: Unfair taxes, unfair schools: The New Hampshire way

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Politics

New Hampshire school phone ban could be among strictest in the country

When Gov. Kelly Ayotte called on the state legislature to pass a school phone ban in January, the pivotal question wasn’t whether the widely popular policy would pass but how far it would go.

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Arts & Life

Young Professional of the Month Cady Hickman: Harmonizing Marketing, Marathons and Meaningful Moments

Meet Cady Hickman, a marketing specialist who lives in Manchester and works at Rumford Stone in Bow. Her talents stretch far beyond the office. As a proud Concord Rotarian and PR Chair, co-founder of Queen City Improv and a national performer, Cady brings creativity and connection to every role she takes on. She travels the country singing the national anthem at marathons through her initiative, “Cady Sings & Strides,” and was named to the Union Leader’s 40 Under Forty Class of 2021.

Artist spotlight: Jackie Hanson

Artist spotlight: Jackie Hanson

A sneak peak of summer events in the Concord area

A sneak peak of summer events in the Concord area

Pierce Manse reopens for the season

Pierce Manse reopens for the season

Obituaries

Donna Lee Rust

Donna Lee Rust

Donna Lee (Raymond) Rust Concord, NH - Donna Lee (Raymond) Rust, 81, passed away on June 5, 2025 at Pioneer Valley Health & Rehabilitation in South Hadley after suffering a recent neck injury, and enduring many years with dementia. Born ... remainder of obit for Donna Lee Rust

John Pooler Jr.

John Pooler Jr.

John Pooler Jr Daytona , FL - John P. Pooler Jr. passed away January 10, 2025, in Daytona Florida, after a brief illness. John was born in Concord, NH to John Sr. and Nancy (Cournoyer) Pooler on June 30th, 1961. John attended MVHS in Pe... remainder of obit for John Pooler Jr.

Douglas G. Richards

Douglas G. Richards

Bow, NH - Douglas Gilbert Richards was born in Concord, NH on March 24, 1944. Doug spent the majority of his next 81 years roaming the New England area he so deeply loved. Above all, the central feature of Doug's life was forming and nu... remainder of obit for Douglas G. Richards

Richard E. Neilson

Richard E. Neilson

Nashua, NH - Richard "Rick" Neilson, 81, passed away on June 9, 2025 after a long illness. Rick was the son of the late Perley Neilson and Bernice (Funk) Procopio and Joseph Procopio. Born and raised in Pittsfield, MA, Rick attended Pit... remainder of obit for Richard E. Neilson

Pembroke Academy graduation: ‘We are equally deserving of this’

Pembroke Academy graduation: ‘We are equally deserving of this’

New Hampshire leads nation in child well-being, lags in student proficiency

New Hampshire leads nation in child well-being, lags in student proficiency

Boys’ Lacrosse: Coe-Brown defeats Hawks in semis, 14-7, to advance to first championship in program history

Boys’ Lacrosse: Coe-Brown defeats Hawks in semis, 14-7, to advance to first championship in program history

Hiker rescued off Mt. Washington as temperatures approached freezing

Hiker rescued off Mt. Washington as temperatures approached freezing

Opinion: Thoughts about our kids after nine years on the road

Opinion: Thoughts about our kids after nine years on the road

High Range coming to Henniker Concert Series

High Range coming to Henniker Concert Series

Where lawmakers disagree: Here are the last few issues still getting hashed out in the State House

Where lawmakers disagree: Here are the last few issues still getting hashed out in the State House

New hangar for private planes coming to Concord airport

New hangar for private planes coming to Concord airport

Flights to JFK from Manchester start Friday

Flights to JFK from Manchester start Friday

Baseball: Bishop Brady advances to first final since 1989, Belmont falls in D-III semis

Baseball: Bishop Brady advances to first final since 1989, Belmont falls in D-III semis Baseball: John Stark delivers dream scenario in 9-0 semifinal win

Baseball: John Stark delivers dream scenario in 9-0 semifinal win Girls’ lacrosse: ‘Who would have thought?’ – Pride team reflects on first state championship appearance in program history

Girls’ lacrosse: ‘Who would have thought?’ – Pride team reflects on first state championship appearance in program history Opinion: Our leaders’ puzzling decision to eliminate the State Council on the Arts

Opinion: Our leaders’ puzzling decision to eliminate the State Council on the Arts Concord became a Housing Champion. Now, state lawmakers could eliminate the funding.

Concord became a Housing Champion. Now, state lawmakers could eliminate the funding. ‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference

‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference  Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide White Mountain art exhibition makes new home at New Hampshire Historical Society

White Mountain art exhibition makes new home at New Hampshire Historical Society