‘A sense of relief’ — Amid rising tensions over immigration, over 70 newly naturalized citizens rejoice at Concord ceremony

Dinorah Mull hadn’t thought twice about her three decades in the United States.

‘We need all of you’ – New Hampshire lacks more foster families. Local recruitment efforts are trying to change that

Before Maddie Lemay went to prom, she had a checklist of adults she needed to ask for permission.

Most Read

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

The Appalachian Trail in New Hampshire just got easier, as another debate looms over replacing structures in wilderness areas

The Appalachian Trail in New Hampshire just got easier, as another debate looms over replacing structures in wilderness areas

Two Weare select board members resign

Two Weare select board members resign

Thirst place: Concord maintains its drinking water dominance

Thirst place: Concord maintains its drinking water dominance

Lawsuit: Former Belmont High student alleges principal failed to stop sexual abuse by teacher in 2009

Lawsuit: Former Belmont High student alleges principal failed to stop sexual abuse by teacher in 2009

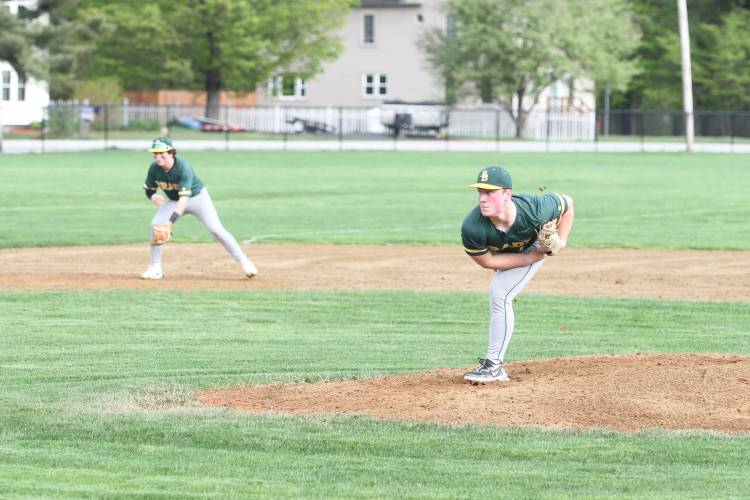

Baseball: Syvertson suits up for CCA in narrow win over Franklin

Baseball: Syvertson suits up for CCA in narrow win over Franklin

Editors Picks

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

‘We honor your death’ – Arranging services for those who die while homeless in Concord

‘We honor your death’ – Arranging services for those who die while homeless in Concord

Sports

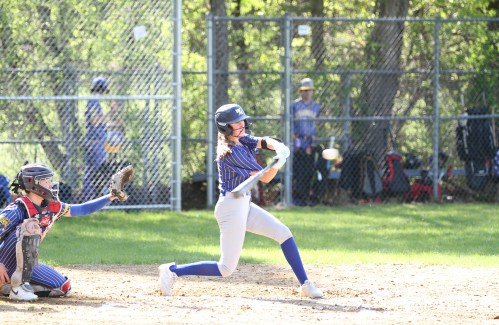

High schools: Tuesday’s baseball, softball, lax, tennis and track results

Bishop Brady 16, Kearsarge 5

Baseball: Syvertson suits up for CCA in narrow win over Franklin

Baseball: Syvertson suits up for CCA in narrow win over Franklin

High schools: Monday’s softball, baseball, lax, tennis and track results

High schools: Monday’s softball, baseball, lax, tennis and track results

High schools: Weekend lacrosse results

High schools: Weekend lacrosse results

High schools: Thursday’s softball, baseball, lax and track results

High schools: Thursday’s softball, baseball, lax and track results

Opinion

Opinion: My memories of Vietnam 50 years later

Jean Stimmell, retired stone mason and psychotherapist, lives in Northwood and blogs at jeanstimmell.blogspot.com.

Opinion: Concord officials: Can we sit and talk?

Opinion: Concord officials: Can we sit and talk?

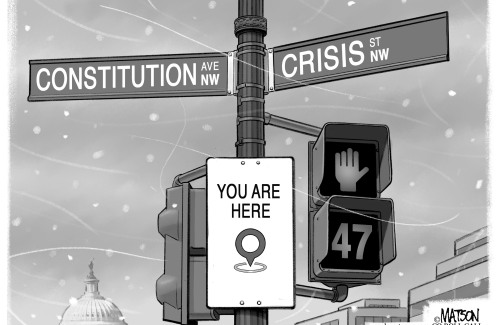

Opinion: Trump versus the U.S. Constitution

Opinion: Trump versus the U.S. Constitution

Opinion: Protect our winters!

Opinion: Protect our winters!

Opinion: That was then. This is now.

Opinion: That was then. This is now.

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Politics

‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference

Rosemarie Rung thinks of Elijah Lewis often.

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Arts & Life

Donating “The Bibliophile”

On April 26, Tom Barber, an Andover resident and a well-known painter and illustrator since the 1970s, presented his painting of "The Bibliophile" to Michaela Hoover, director of the Andover Libraries.

Spring things: Savoring the small moments

Spring things: Savoring the small moments

Pembroke City Limits brings yoga, book club, line dancing, and more to Suncook Village

Pembroke City Limits brings yoga, book club, line dancing, and more to Suncook Village

The Last Stand Country Band performing in Allenstown

The Last Stand Country Band performing in Allenstown

Obituaries

Marilyn Batchelder

Marilyn Batchelder

Marilyn (Kress) Batchelder Allenstown, NH - Marilyn (Kress) Batchelder, age 77 died on Saturday May 10 at Concord Hospital. She was the daughter of the late Richard and Gloria (Dion) Kress. She was born and raised in Manchester and grad... remainder of obit for Marilyn Batchelder

George W. Bean

George W. Bean

Concord, NH - A celebration of life for George W. Bean who passed away on February 27th, 2025, will be held on Saturday May 17th, 2025, from 1PM to 5PM at his and Jane's home at 42 Fisherville RD, Concord NH ... remainder of obit for George W. Bean

Sarah Kinter

Sarah Kinter

Canterbury, NH - Surrounded by the home of her dreams in Canterbury, New Hampshire and eager to begin the new journey before her, Sarah Anne Kinter left this life on Thursday, May 8, 2025, to start joyously "partying upstairs", after ei... remainder of obit for Sarah Kinter

Janet R. Boisvin

Janet R. Boisvin

Concord, NH - Janet R. Boisvin, 81, died peacefully at her home on Thursday, May 08,2025 after a period of failing health. The daughter of the late Elwin and Violet Jenkins, Janet was born on August 28,1943 in Concord. She was a gr... remainder of obit for Janet R. Boisvin

Senate stalls bill that would’ve eliminated annual car inspections in New Hampshire

Senate stalls bill that would’ve eliminated annual car inspections in New Hampshire

Young Professional of the Month Katie Duncan shares about creativity, community, connection

Young Professional of the Month Katie Duncan shares about creativity, community, connection

‘Customer service is my top priority’ – New town administrator to take office in Hopkinton next month

‘Customer service is my top priority’ – New town administrator to take office in Hopkinton next month

Tiny Tapestry sale at Red River Theaters raising money for Concord Coalition to End Homelessness

Tiny Tapestry sale at Red River Theaters raising money for Concord Coalition to End Homelessness

Bowling for a cause: Angelman Syndrome Fundraiser coming to Boutwell’s

Bowling for a cause: Angelman Syndrome Fundraiser coming to Boutwell’s

Beautify Allenstown hosting community cleanup day

Beautify Allenstown hosting community cleanup day

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week

Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week On the Trail: Shaheen’s retirement sparks a competitive NH Senate race

On the Trail: Shaheen’s retirement sparks a competitive NH Senate race Brookford Farm’s annual heifer parade celebrates family, sustainability, organic farming

Brookford Farm’s annual heifer parade celebrates family, sustainability, organic farming