As the climate goes haywire, can flood-control dams keep up?

| Published: 08-02-2024 2:20 PM |

The back-to-back 100-year floods that swept through the North Country after ravaging Vermont might raise your concern about how New Hampshire’s aging flood-control dams are coping as extreme precipitation becomes more common, less predictable and more dangerous.

Here’s one indication that worry might be misplaced: Dry spillways in state dams.

“The auxiliary spillways are designed to hold several feet of flow (during floods) but they have never had significant flow at all,” not even during big floods, said Matt Brown, state conservation engineer for Natural Resources Conservation Service in New Hampshire. “They have protected downstream towns for a while now. They were designed very conservatively.”

Brown was speaking of the 28 flood-control dams that New Hampshire owns, mostly in the Baker River valley in the White Mountains and the Souhegan River valley in the Monadnock Region. They were built in the 1960s and early ‘70s on small tributaries by what was then the federal Soil Conservation Service, in response to a series of floods over the decades.

These are passive dams lacking flashboards, not much more than earthen berms with a couple of overflow outlets called spillways that created retention ponds of less than 20 acres, often much less. They’re designed to slow down a deluge before it can damage property rather than hold it back entirely.

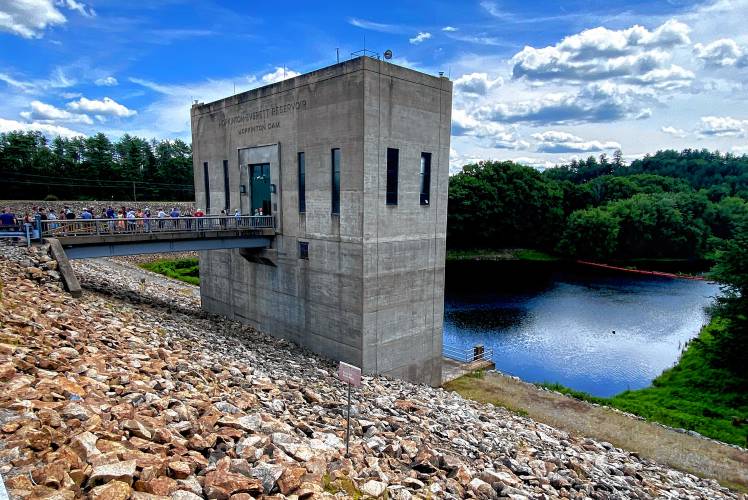

They differ from the seven much bigger dams built by the Army Corps of Engineers around the state. These include the Blackwater Dam in Webster, opened in 1941, which can hold back floodwaters that extend seven miles upstream, covering 3,500 acres, and the huge Hopkinton-Everett system, opened in 1962 with dams in Hopkinton and Weare that create two lakes connected by canals that can retain 58 billion gallons of water.

The Corps of Engineers flood-control dams aren’t just big, they’re also actively managed, with gates that are opened and shut to hold or release water based on data from automatic gauges that tell what’s flowing in streams and tributaries around the state.

“If those gauges that we have in strategic locations show that they’re going to be hitting flood stage, that’s when we will cut back our flows significantly. Or if it’s going to be like a major flood stage then that’s when we go into those bare minimum gate settings. Not until those gauging stations start to recede and fall below flood stage will we start to slowly release water from both reservoirs to make room in case there’s another storm,” said Stephen Dermody, project engineer for Hopkinton-Everett Lakes, during a recent tour.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

What’s the best way to get to New York City? We tested one of the new options for Concord-area residents.

What’s the best way to get to New York City? We tested one of the new options for Concord-area residents.

Flames engulf Chichester home, sending two people to the hospital

Flames engulf Chichester home, sending two people to the hospital

U.S. Rep. Maggie Goodlander buys home in Concord, in NH’s second district

U.S. Rep. Maggie Goodlander buys home in Concord, in NH’s second district

Marshalls coming to Merchants Way at Exit 17

Marshalls coming to Merchants Way at Exit 17

Shaun St. Onge, a former coach and administrator at Merrimack Valley High School, will serve as the school’s next principal

Shaun St. Onge, a former coach and administrator at Merrimack Valley High School, will serve as the school’s next principal

Database: Enrollment of each private school in New Hampshire since the Education Freedom Account program started

Database: Enrollment of each private school in New Hampshire since the Education Freedom Account program started

The tour was of the gatehouse that controls flows from the Contoocook River into the lakes, located alongside Maple Street, Route 127, as it crosses over the river.

Dermody said the system always allows some water through to sustain fish habitat and aquatic life downstream.

“If we were to have a large storm event … we will close with flood control gates at both the Everett Dam in Weare in the Hopkinton Dam in Hopkinton, down to our minimum outflow. And then we’ll continue to hold that and we’ll build a large lake behind both dams,” he said.

“Here at Hopkinton, once we get about 20 feet higher than normal, then water starts to flow through a series of canals that will start to send water down to the Everett reservoir. Hopkinton Dam and the Everett Dam during smaller flood events, they work independently of each other, but if we were to have a really large flood event like a hurricane, then the two lakes combine to form one giant reservoir,” he said.

During the Mother’s Day flooding in 2006, “staff here were actually able to take a boat from the Everett Dam and come all the way up to the office here in Hopkinton.”

Even passive earthen berms need maintenance, from making sure that groundhogs don’t dig burrows in the dam itself to keeping trees out of spillways, and after 60 years they may need upgrading.

“These structures are coming up in age to which rehabilitation needs to occur,” said Corey Clark of the state’s Dam Bureau.

Funding for the work from the Natural Resources Conservation Service dates back to 2012. The state has done preliminary assessments on all its dams, Clark said, with independent consultants looking at data like discharge histories and what has changed downstream, and then has ranked them by need. A dam known as Baker River Site 8 is the first to move into the phase of design and construction while several dams around the upper Souhegan River are next in line.

A major component of the rehabilitation involves those spillways, which start draining the retention pond when water has risen to within some 10 feet of the dam height. They keep water from over-topping the dam, which could quickly erode the earthen structure and lead to collapse.

“We are planning to replace these spills with some concrete linings … to be really, really robust,” Clark said.

Being really robust is only going to become more important. A warming atmosphere can hold more moisture, which means it can release more moisture at any time, and climate change is altering weather patterns in unpredictable ways, making it harder to be prepared. The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration is constantly tweaking the data used to classify storms such as the 100-year-flood designation, trying to keep up.

Clark said the state dams were designed to be safe up to a “Noah’s Ark flood,” around a 30-inch downfall in one storm. “That’s based on old data, for sure, and that goalpost could move but we haven’t come close to 30-inch rainfall.”

It would, of course, be possible to upgrade the dams to withstand even bigger floods but that’s not cheap.

“It’s hard to spend precious tax dollars on something that doesn’t exist yet … and might not,” Clark pointed out.

Finalizing the budget: What to look for in the State House this week

Finalizing the budget: What to look for in the State House this week Bow offers water to Hooksett plant, asks Concord to help fix its supply

Bow offers water to Hooksett plant, asks Concord to help fix its supply Hyper-local, good-news-only paper in Andover is closing

Hyper-local, good-news-only paper in Andover is closing Concord Christian Academy celebrates accomplishment and faith at graduation ceremony

Concord Christian Academy celebrates accomplishment and faith at graduation ceremony