Mental health, attitude and behavior shifts make it tougher for schools to tackle learning gaps

| Published: 04-04-2022 6:03 PM |

Noah Lira took his job as a social studies teacher at Franklin High School to spark enthusiasm for subjects he loves, and to make a difference. Then COVID-19 hijacked the world, taking education with it.

After 18 months of remote and hybrid learning, schools in Franklin and across New Hampshire have returned to in-person learning, with student desks further apart, masks optional, and an edgy mixture of uncertainty, energy, and relief.

Teachers are shouldering wider and deeper loads as they address social, emotional and academic gaps, which time and extra help may narrow. Most impacted are the students – including in how they view themselves, their place in the world, and how they fit back into their school.

In the post-COVID landscape, an attitude shift among students is muting the colors.

“I’m dealing much more with complete apathy,” said Lira, who commutes from Derry to work in Franklin, a district where family dynamics, substance misuse and income loss can conspire against learning – and where students appreciate his help and encouragement. In COVID’s wake, many sophomores seem to be a year behind, said Lira, and more one-on-one attention is required. “I feel like I have freshmen with me,” he said.

It’s a universal challenge, certainly one not confined to New Hampshire’s smallest city.

As education regroups after more than a year on screen, learning loss tops the list of problems to tackle as schools take stock of delays and deficits – and ponder what will jumpstart student interest and bring kids back to pre-pandemic competency levels.

Gaps for one student may differ substantially from someone in the same class, and shortfalls in learning aren’t always instantly apparent, or quick to eradicate.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

By all appearances, Canadians are leery of coming to NH

By all appearances, Canadians are leery of coming to NH

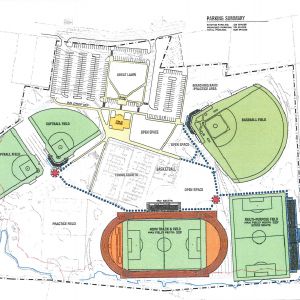

Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project

Plans advance on $27M Memorial Field project

“A dream come true” – Family opens housing for adults with disabilities in Concord

“A dream come true” – Family opens housing for adults with disabilities in Concord

Memorial Day events in the Concord area

Memorial Day events in the Concord area

Giving life back to board sports: Back Alley Boards upcycles boards into art

Giving life back to board sports: Back Alley Boards upcycles boards into art

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

“Probably everyone has experienced some sort of learning loss,” said Kirk Beitler, school superintendent in Gilford, which, like other New Hampshire school districts, uses federal ESSER relief funds to provides a mix of tutoring and expanded extra help, including during empty periods in student schedules, before and after school, and in summer enrichment programs. “We’re juggling a lot of different balls to best meet their needs,” he said.

Frequently, the social and emotional challenges gripping students are making the journey rougher.

“There’s a heightened sense of anxiety because of the unknown,” said Brianna Vandell, who teaches fourth through sixth grade at Franklin Middle School. “As much as we provide consistency and predictability in the classroom,” the world outside has become shakier. In general, it’s been harder for more students to pay attention and concentrate in class, she said. Even for adults, tuning out a whirlwind of worries and what-ifs can be a tough climb. “For a child who hasn’t learned these skills yet, it can be more difficult,” Vandell said.

To determine what students have missed and what they now need for support, administrators rely on what teachers, counselors, students and parents report, plus in-school performance, and attendance and discipline records. Standardized test scores before and after COVID give clues to changes in accumulated and retained learning.

So far, NH school tests scores have echoed nationwide trends, and Granite State students seem to have suffered fewer setbacks in the areas of language arts than their counterparts in other states. In 2021, statewide standardized test scores showed the number of students who score proficient or better dropped by 10% in math – from 48% before the pandemic to 38 last year. In language arts, the proficiency-and-above percentage dropped from 59 to 52%.

The score range can vary for different districts and grade levels, and certainly between different children. In general, girls, the youngest kids, and children from low-income families were more adversely affected academically by the loss of in-person school and the switch to remote. But almost all children suffered some delays, and some form of social and emotional fallout from not learning with peers in person.

In many schools, including in the Lakes Region, student engagement is lagging, attendance numbers are wobbly, and behavior problems are up.

Some students “who don’t normally act out are acting out. Kids that normally act out are keeping to themselves,” Vandell said of middle school students. “We’ve seen some defiance, some opposition. For some kids it’s a sense of apathy. They’re kind of like, ‘Whatever.’ Sometimes there’s a heightened sense of focus. We have to say, ‘Take a deep breath. You can have fun.’”

“The biggest difference is it’s much harder for kids to show up in a classroom and be ready to learn,” said Barbara Slayton, student wellness coordinator for Franklin Schools. “The time out of the classroom had a disproportionate effect on kids that came from different places” socially and economically, she said. For many kids, school functions as an equalizer, providing structure, safety, balanced meals and responsible adults – benefits that were lost, along with student interest, when education went online.

Teachers are contemplating and trying multiple strategies to reel students back. One tactic of Lira’s has proven valuable: remodeling otherwise dry subjects to help them see new relevance, and take a longer-term view. In Lira’s Ancient Philosophy class, tenth graders learned how marketing, advertising and technology, including social media, are used to manipulate beliefs and behavior – and get people to spend money.

Lira turned philosophy into a marketing project. His students role played working for advertising agencies, trying to sell Confucianism and Taoism, traditional Chinese beliefs, and investigated what is appealing or not so appealing about them. Students “looked at how marketing and advertising are used in commercials and billboards, while learning the philosophies of ancient cultures,” he said.

That basic recipe has worked with reluctant learners, and with the post-COVID level of student skepticism and lack of engagement in school, it may have doubled in value.

“It’s been a tough couple of years,” said New Hampshire Commissioner of Education Frank Edelblut. “Kids are a little lethargic, and some are wondering, ‘What’s the point?’ There’s irrefutable evidence that when students are connected to learning, and can put it to a purpose, it works better.” – including to break down apathy and resistance.

“The years of COVID and the ones we’re in now have made it important to make school relevant,” echoed Superintendent Steve Tucker of Laconia schools.

After being steeped in online substitutes and functioning solo at home, many students require a motivation reset. “That was a perception, that Zoom was a technique to get students engaged and baby sat,” said Lira. There was less perceived pressure to participate or perform. Some kids got used to turning off cameras so they could do something else. They grew accustomed to having more time, and acquired a sense that schoolwork was almost optional or could be postponed. Now they have returned to stricter routines, time constraints and expectations.

”I think the structure of school has ricocheted on us as well as them,” said Lira. “We’re having to bring students back from watching TV, TikTok and video games. To bring attention back, you have to be very entertaining, and an interesting person,” he said. “There are only so many ways you can make algebra interesting” for kids who don’t gravitate toward math.

This year, more students have individualized education programs in schools, and in many cases demand for accommodations through special education services has risen sharply. That includes students who are allowed extra time for tests and assignments or take standardized tests alone in a quiet room, or get time out from class for documented emotional reasons, in addition to larger, more complex accommodations.

At Laconia Middle School, in October 2019, 79 students were identified for special education services, compared to 102 projected for the 2022-23 school year. At Laconia High School, those numbers jump from 77 to 110.

Tucker said principals at each of Laconia’s schools are reporting more acute behaviors and more profound needs for a small number of students. At Laconia High School, behavior or discipline referrals climbed from 847 during the 2018-2019 academic year to 1121 so far in 2021-22. At other Laconia schools, those referral numbers appear to be declining, he said.

There’s a greater push now to make the education work for struggling and drifting kids, and to resell school as something immediate and useful – not just a box to check off on the list of life – and to match student skills and interests to attainable, visible goals.

“What do we need this for in real life? Why is it important to me today? It’s the fundamental question that teachers have to keep in mind,” said Lira. “Why is it important to learn about any of this stuff?”

Increasingly, the answer must go beyond becoming a well-rounded person, he said.

Relationship building is key. “We need to build that trust, that we’re going to grow together,” said Lira.

Parents need to team up with teachers, said Vandell at Franklin Middle School.

“Become a partner with your child’s teacher. It shows kids it’s not just the teacher who values education. Be in communication so that parents and teachers are working together to support the child in whatever ways the child needs. I’ve had parents call and say they had an awesome basketball game or a rough night at home. Being in partnership, everyone can show that education is valued,” she said. That will speed the education reset, bolster personal direction and student goal-setting, and open up folders of hope.

“Children will learn in different ways at different paces. Make sure you’re celebrating your kid’s wins and not comparing them to other kids’ wins,” Vandell said. “It’s an interesting age whether or not we’re in a pandemic. This is the age when children are discovering who they are.”

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.]]>

‘The smiles say it all’: Sweet Dreamz brings creative soft-serve to Penacook

‘The smiles say it all’: Sweet Dreamz brings creative soft-serve to Penacook  Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now?

Drought is completely gone from New Hampshire – maybe it can stop raining now?