Opinion: Remember the ladies

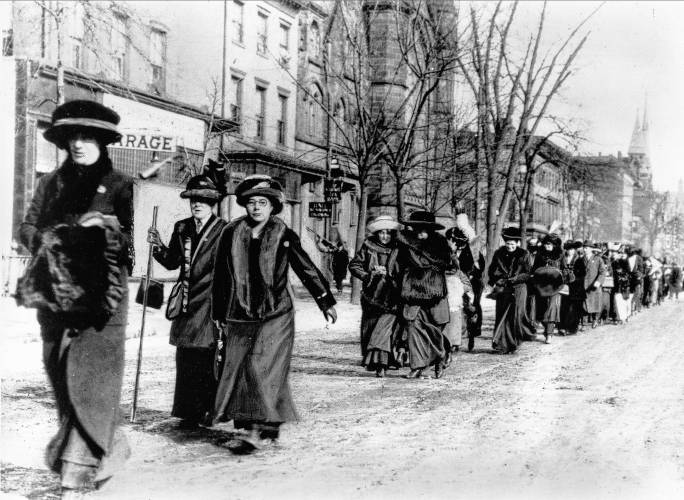

Suffragists led by “General” Rosalie Jones march from New York on their way to the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington D.C., on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inaugural in March 1913. AP

| Published: 03-22-2024 9:19 AM |

Jean Lewandowski is a retired special needs teacher. She lives in Nashua.

In 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John in Philadelphia, “I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.”

As we know, the Founders forgot the ladies. Few 18th-century men took seriously the idea that the “people of the United States” included women, and it wasn’t until the 20th-century that women had guarantees of basic rights like obtaining loans, signing contracts, or even bodily autonomy. It wasn’t until 1993 that spousal rape was ruled a crime in all state and federal law.

It was the 130-year-long campaign for women’s suffrage that made even this slow progress possible. The 1789 Constitution gave states the power to determine voting requirements. Many colonial women had enjoyed voting rights, but after the revolution, only New Jersey allowed woman suffrage— then rescinded it in 1807. In the next 60 years, women convinced some state legislatures to reinstate partial voting rights.

Recognizing there is no such thing as partial equality, the Seneca Fall, NY, convention of 1848 created a Declaration of Sentiments modeled after the Declaration of Independence, and produced a plan to amend the U.S. Constitution. In 1878, suffragists’ male allies in Congress finally proposed the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which has the crispness of exasperated women everywhere who have had enough of our shenanigans: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

It was voted down in 1878 and in every Congress thereafter for the next 40 years.

Generations of ladies persisted. They organized, campaigned, secured funding, lobbied all-male legislatures, marched, and demonstrated. There were dire warnings these man-haters represented perversions of natural order and divine will, and they would destroy America. Suffragists were routinely spat on, shouted down, demonized, and arrested.

As their efforts slowly progressed, opposition violence increased. In January 1917, “Silent Sentinels” began picketing for equal rights outside the White House. Hundreds of women were arrested, and some who were jailed went on hunger strikes. On Nov. 10, around 30 sentinels protesting the force-feeding of jailed suffragists were taken to the Occoquan Workhouse. On Nov. 14, the superintendent of the workhouse ordered guards to attack them. They beat, choked, kicked, chained, and slammed women against the iron furniture.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Youth rally against New Hampshire’s bill allowing medical aid in dying

Youth rally against New Hampshire’s bill allowing medical aid in dying

As site testing begins on new middle school site, activists file to put location debate on the ballot

As site testing begins on new middle school site, activists file to put location debate on the ballot

Lawyers and lawmakers assert the Department of Education is on the verge of violating the law

Lawyers and lawmakers assert the Department of Education is on the verge of violating the law

A May tradition, the Kiwanis Fair comes to Concord this weekend

A May tradition, the Kiwanis Fair comes to Concord this weekend

Neighboring landowner objection stalls Steeplegate redevelopment approval

Neighboring landowner objection stalls Steeplegate redevelopment approval

State senator passes out on senate floor

State senator passes out on senate floor

It’s no accident that 1960s civil rights leaders adopted the suffragist strategy of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience. The barbarity of this “Night of Terror” exposed the brutality required to subjugate free people and mobilize support for women. State after state approved voting rights amendments, and in January of 1919, suffragists lit and guarded a Watchfire for Freedom near the White House that burned continuously until both the House and Senate passed the 19th Amendment in May and June.

The Constitution then requires ratification by ¾ of state legislatures, 36 at the time. By the summer of 1919, 35 states had ratified. Tennessee would be the 36th. Author Elaine Weiss paints a vivid picture in her book “The Woman’s Hour” of the battle for that final state. Suffragists (“Suffs”) from around the country met in Nashville to lobby for a special legislative session. Politicians, clergy, industrialists, conservative newspapers, and white supremacists who feared Black women’s votes tried by rhetorical and financial persuasion to convince leaders not to convene, but just enough men stood firm, and the battle for votes commenced.

Besides powerful men, Suffs were opposed by the “Antis,” women and men who believed it was women’s place to tend the moral high ground, rather than be sullied by politics. Ironically, it was the Antis who concocted a libelous story about Suff leaders and threatened to send it to a conservative newspaper. That plot was foiled, but there were still dirty tricks, threatening phone calls, and shifting alliances to combat, and racial anxiety permeated everything. One congressman warned during a floor debate, “Just as soon as this 19th Amendment…is put upon a state like Georgia, Hell’s going to break loose.”

It was another letter that sealed the deal. A young congressman named Harry Burn held the deciding vote, and both colleagues and constituents made it clear his career was on the line. He turned to a note he carried in his pocket for guidance: “Dear Son, Hurrah and vote for suffrage, and don’t keep them in doubt…. With lots of love, Mama.” The ayes held for Tennessee, and Congress ratified the 19th Amendment on August 18th, 1920.

Women weren’t given the right to vote; suffragists won that right. In this “post-Roe” era, when our bodily autonomy is again at risk, we can honor them by taking our turn tending the Watchfire for Freedom.

Carrie Catt, a giant of the suffrage movement, wrote after winning Tennessee, “Women have suffered agony of soul you can never comprehend, that you and your daughters might inherit political freedom…. The vote is a power, a weapon of offense and defense, a prayer. Use it intelligently, conscientiously, prayerfully. Progress is calling to you to make no pause. Act!”

Opinion: Brown v. Board of Education and the Claremont Lawsuit

Opinion: Brown v. Board of Education and the Claremont Lawsuit Opinion: Our responsibility to care for the most vulnerable among us

Opinion: Our responsibility to care for the most vulnerable among us Opinion: New Hampshire’s LGBTQ+ Youth need support, not political attack

Opinion: New Hampshire’s LGBTQ+ Youth need support, not political attack Opinion: Seeing the full picture: Optometry can increase access to care

Opinion: Seeing the full picture: Optometry can increase access to care