‘Perfect fit’: Fabulous Looks Boutique shifts leadership, preserving brands and styles

Fabulous Looks has been a home away from home for owner Sherry Spurr for over 30 years.

Concord National LL Softball wins State Championship and moves on to Little League Regional Tournament

The Concord National Youth Softball 12U All-Stars team booked a trip down to Bristol, Conn., to represent New Hampshire in the Little League New England Region Tournament for the second year in a row with a win over Mount Monadnock on Saturday, 13-3.

Most Read

Concord may finally buy long-closed rail line with hopes of creating city-spanning trail

Concord may finally buy long-closed rail line with hopes of creating city-spanning trail

New Cheers owners honor restaurant’s original menu while building something fresh

New Cheers owners honor restaurant’s original menu while building something fresh

A look ahead at the ‘preferred design’ for Concord’s new police headquarters

A look ahead at the ‘preferred design’ for Concord’s new police headquarters

New Hampshire targets sexual exploitation and human trafficking inside massage parlors

New Hampshire targets sexual exploitation and human trafficking inside massage parlors

State rules Epsom must pay open-enrollment tuition to other school districts, despite its refraining from the program

State rules Epsom must pay open-enrollment tuition to other school districts, despite its refraining from the program

Editors Picks

A Webster property was sold for unpaid taxes in 2021. Now, the former owner wants his money back

A Webster property was sold for unpaid taxes in 2021. Now, the former owner wants his money back

Report to Readers: Your support helps us produce impactful reporting

Report to Readers: Your support helps us produce impactful reporting

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

City prepares to clear, clean longstanding encampments in Healy Park

Productive or poisonous? Yearslong clubhouse fight ends with council approval

Productive or poisonous? Yearslong clubhouse fight ends with council approval

Sports

Youngsters Richardson and Hakala move on, and veterans crash out at 122nd State Amateur Championship

ROCHESTER — Every golfer has A routine. Superstitions, lucky charms and a specific way of finding a mental sweet spot aren’t specific to the sport.

Athlete of the Week: Grace Saysaw, Concord High School

Athlete of the Week: Grace Saysaw, Concord High School

Local golfers tee off at 122nd Amateur Championship

Local golfers tee off at 122nd Amateur Championship

Opinion

Opinion: Trumpism in a dying democracy

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today

Opinion: What Coolidge’s century-old decision can teach us today

Opinion: The art of diplomacy

Opinion: The art of diplomacy

Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community

Opinion: After Roe: Three years of resistance, care and community

Opinion: Iran and Gaza: A U.S. foreign policy of barbarism

Opinion: Iran and Gaza: A U.S. foreign policy of barbarism

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Politics

New Hampshire school phone ban could be among strictest in the country

When Gov. Kelly Ayotte called on the state legislature to pass a school phone ban in January, the pivotal question wasn’t whether the widely popular policy would pass but how far it would go.

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Arts & Life

Artist Spotlight: Holly Emrick

This week’s artist spotlight, brought to you through a collaboration with the Concord Insider and the Concord Arts Market, focuses on Holly Emrick, who lives in Boscawen. A 58-year-old mother of two and grandmother of two and a wife of 40 years, Emrick discovered jewelry-making during her 16 years as a stay-at-home mom.

Nate Lavallee, July Young Professional of the Month: Stretching toward strength, self-care and Southern NH wellness

Nate Lavallee, July Young Professional of the Month: Stretching toward strength, self-care and Southern NH wellness

Lavender haze: Purple fields bloom at Warner farm

Lavender haze: Purple fields bloom at Warner farm

Arts in the Park returns for July

Arts in the Park returns for July

Hopkinton art gallery showcases “Creativity Beyond Convention”

Hopkinton art gallery showcases “Creativity Beyond Convention”

Obituaries

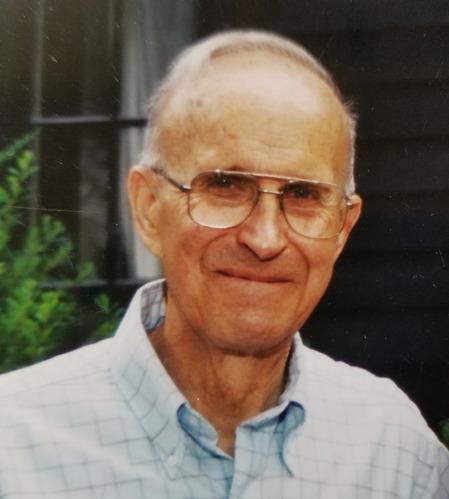

Arnold Stetson

Arnold Stetson

Arnold "Stet" Stetson Elkins, NH - Arnold "Stet" E. Stetson, 90, of Wilmot Center Road, died Sunday, July 13, 2025 at his home. He was born in East Andover, NH on December 30, 1934 the son of Richard F. and Martha (Crewe) Stetson. H... remainder of obit for Arnold Stetson

John W. Herbert

John W. Herbert

Salisbury, NH - John W. Herbert, a proud Navy veteran, devoted family man, and longtime member of the Salisbury community, passed away peacefully on June 28, 2025, at the age of 82. Born and raised in City Island in the Bronx, New York... remainder of obit for John W. Herbert

Sharon Sargent

Sharon Sargent

Concord, NH - Sharon Mitchell Sargent of 33 Christian Avenue in Concord passed away on July 11, 2025 following a brief illness. Born on October 18, 1944 in Lynn, MA, Sharon, a long-time resident of Gilford, NH was the daughter of Paul ... remainder of obit for Sharon Sargent

Herbert Little

Herbert Little

Concord, NH - Herbert E. "Herb" Little died on the evening of July 6, 2025, at Havenwood Heritage Heights in the room he shared with his loving wife Debby who was, as always, by his side. He was 97 years old having been born on Septembe... remainder of obit for Herbert Little

Concert on the lawn coming to Pierce Manse

Concert on the lawn coming to Pierce Manse

Free speech group, residents back Bow parents’ free speech appeal in case involving transgender athletes

Free speech group, residents back Bow parents’ free speech appeal in case involving transgender athletes

Opinion: What does redemption really mean?

Opinion: What does redemption really mean?

ZBA appointment to be reconsidered at Monday Council meeting

ZBA appointment to be reconsidered at Monday Council meeting

Opinion: As people of faith, the state budget offends our values

Opinion: As people of faith, the state budget offends our values

As Concord’s Gavin Richardson places second at golf Junior Amateur, young players look ahead to the 122nd State Amateur Championship

As Concord’s Gavin Richardson places second at golf Junior Amateur, young players look ahead to the 122nd State Amateur Championship Sunapee’s Bryce Whitlow keeps memory of above-average MLB players alive through social media page ‘MLB Hall of (Pretty) Good’

Sunapee’s Bryce Whitlow keeps memory of above-average MLB players alive through social media page ‘MLB Hall of (Pretty) Good’ Concord became a Housing Champion. Now, state lawmakers could eliminate the funding.

Concord became a Housing Champion. Now, state lawmakers could eliminate the funding. ‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference

‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference  Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide