Historic Tilton Island Park Bridge will be reopened unless Trump takes back a federal grant

The historic Tilton Island Bridge is on track to get repaired after being shut for five years unless the Trump administration decides to yank back a federal grant.

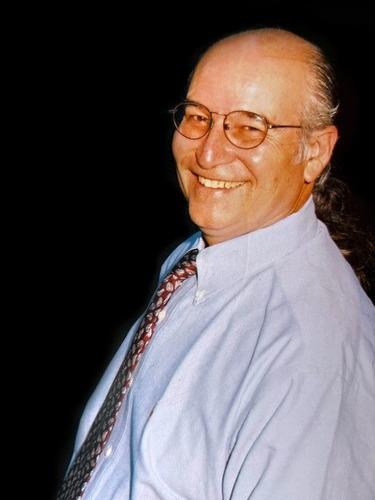

Lyman Cousens, champion of community causes in Boscawen and Concord, dies at 87

The first time Doris Cousens met the man who would become her husband, she didn’t like him.

Most Read

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

‘I thought we had some more time’ – Coping with the murder-suicide of a young Pembroke mother and son

Owners of Lewis Farm prepare to bring back agritourism after long dispute with city of Concord

Owners of Lewis Farm prepare to bring back agritourism after long dispute with city of Concord

‘Folks who use it should pay for it’ — City manager proposes clubhouse plan with smaller tax impact

‘Folks who use it should pay for it’ — City manager proposes clubhouse plan with smaller tax impact

Who would invest in movie theaters these days? These folks

Who would invest in movie theaters these days? These folks

The Appalachian Trail in New Hampshire just got easier, as another debate looms over replacing structures in wilderness areas

The Appalachian Trail in New Hampshire just got easier, as another debate looms over replacing structures in wilderness areas

Concord stargazer puzzled over unidentified flying object

Concord stargazer puzzled over unidentified flying object

Editors Picks

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

The Monitor’s guide to the New Hampshire legislature

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

One year after UNH protest, new police body camera footage casts doubt on assault charges against students

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

‘It’s always there’: 50 years after Vietnam War’s end, a Concord veteran recalls his work to honor those who fought

‘We honor your death’ – Arranging services for those who die while homeless in Concord

‘We honor your death’ – Arranging services for those who die while homeless in Concord

Sports

High schools: Concord girls win elite Merrimack Invitational, MV track sweeps senior day, Winnisquam’s Caruso wins 175th career victory, more results from Thursday

Concord 1st, Coe-Brown 5th

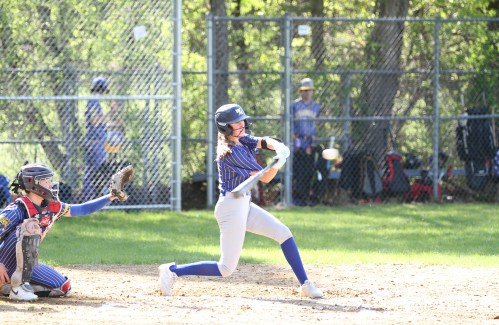

High schools: Tuesday’s baseball, softball, lax, tennis and track results

High schools: Tuesday’s baseball, softball, lax, tennis and track results

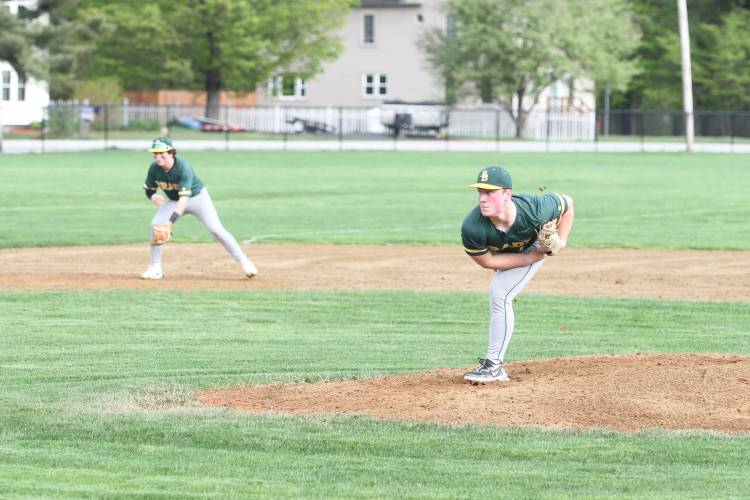

Baseball: Syvertson suits up for CCA in narrow win over Franklin

Baseball: Syvertson suits up for CCA in narrow win over Franklin

High schools: Monday’s softball, baseball, lax, tennis and track results

High schools: Monday’s softball, baseball, lax, tennis and track results

Opinion

Opinion: Where are the permanent solutions for a more stable budget?

Scott Metzger lives in Hopkinton.

Opinion: My memories of Vietnam 50 years later

Opinion: My memories of Vietnam 50 years later

Opinion: Concord officials: Can we sit and talk?

Opinion: Concord officials: Can we sit and talk?

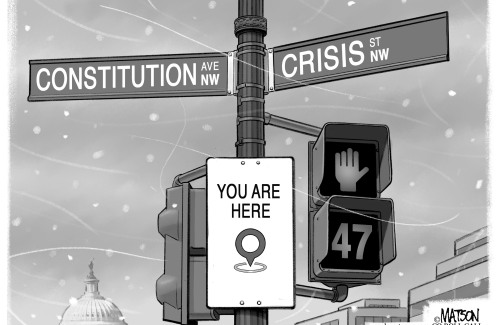

Opinion: Trump versus the U.S. Constitution

Opinion: Trump versus the U.S. Constitution

Opinion: Protect our winters!

Opinion: Protect our winters!

Your Daily Puzzles

An approachable redesign to a classic. Explore our "hints."

A quick daily flip. Finally, someone cracked the code on digital jigsaw puzzles.

Chess but with chaos: Every day is a unique, wacky board.

Word search but as a strategy game. Clearing the board feels really good.

Align the letters in just the right way to spell a word. And then more words.

Politics

‘A wild accusation’: House votes to nix Child Advocate after Rep. suggests legislative interference

Rosemarie Rung thinks of Elijah Lewis often.

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Sununu decides he won’t run for Senate despite praise from Trump

Arts & Life

Young Professional of the Month Katie Duncan shares about creativity, community, connection

Meet Katie Duncan, Membership Manager and Educational Outreach Coordinator at the Capitol Center for the Arts. The 35-year old Concord resident’s passion for the arts and the Concord community shines through her work. From theater stages to local lakes, Katie shares how growing up in Greater Concord shaped her path—and why she’s dedicated to giving back.

Tiny Tapestry sale at Red River Theaters raising money for Concord Coalition to End Homelessness

Tiny Tapestry sale at Red River Theaters raising money for Concord Coalition to End Homelessness

Bowling for a cause: Angelman Syndrome Fundraiser coming to Boutwell’s

Bowling for a cause: Angelman Syndrome Fundraiser coming to Boutwell’s

Beautify Allenstown hosting community cleanup day

Beautify Allenstown hosting community cleanup day

Donating “The Bibliophile”

Donating “The Bibliophile”

Obituaries

Gary Clayton Bedell

Gary Clayton Bedell

Pittsburg, NH - Gary Clayton Bedell, 88, of Pittsburg, NH, passed away peacefully on April 29, 2025, after a lengthy illness, surrounded by his loving family. Born on November 27, 1936, in Lancaster, NH he was the son of the late Cl... remainder of obit for Gary Clayton Bedell

Frederick T. Ford

Frederick T. Ford

Tilton, NH - Frederick "Fred" T. Ford, 87 of Tilton, NH, passed away on Thursday, May 8, 2025, surrounded by his loving family. Born on June 10, 1937, in Jersey City, New Jersey, to the late Frederick V. and Margaret (McNally) Ford. He ... remainder of obit for Frederick T. Ford

Todd Alan Miller

Todd Alan Miller

Penacook, NH - Todd Alan Miller, 61, passed away peacefully at home on April 26th, 2025. He was the beloved son of Donald and Joyce Miller, and a devoted father, grandfather, brother, and friend. Todd graduated from Merrimack Valley Hi... remainder of obit for Todd Alan Miller

Joseph Kimball LaBonte

Joseph Kimball LaBonte

Loudon, NH - It is with heavy hearts that we announce the passing of our brother Joseph Kimball LaBonte, 76, on 1/25/25 at Central Valley Medical Center, Nephi, Utah, after a short period of failing health. He was born 12/2/1948 in Con... remainder of obit for Joseph Kimball LaBonte

Fentanyl, car inspections and parents’ rights: What to look for in the State House this week

Fentanyl, car inspections and parents’ rights: What to look for in the State House this week

As Canadian travel to the U.S. falls, North Country businesses are eyeing this Victoria Day weekend to predict impacts in New Hampshire

As Canadian travel to the U.S. falls, North Country businesses are eyeing this Victoria Day weekend to predict impacts in New Hampshire

High schools: Pelletier scores 100th goal, leads Concord girls’ lax to first win; baseball, softball, boys’ lacrosse and track results from this weekend

High schools: Pelletier scores 100th goal, leads Concord girls’ lax to first win; baseball, softball, boys’ lacrosse and track results from this weekend

Five former Concord Crush girls at St. Paul’s are soon to leave the nest to play NCAA Women’s Lacrosse

Five former Concord Crush girls at St. Paul’s are soon to leave the nest to play NCAA Women’s Lacrosse

Vintage Views: Our very old graves

Vintage Views: Our very old graves

Opinion: In the fight to stop sexual violence, can polio hold the solutions?

Opinion: In the fight to stop sexual violence, can polio hold the solutions?

‘Like going back in time’: Old homes, a train, and a temple added to state historic register

‘Like going back in time’: Old homes, a train, and a temple added to state historic register

Boys’ tennis: Growing the sport, fun and pizza for a tight-knit Concord team on Senior Night

Boys’ tennis: Growing the sport, fun and pizza for a tight-knit Concord team on Senior Night

High schools: Wednesday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse, tennis and track results

High schools: Wednesday’s baseball, softball, lacrosse, tennis and track results Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide

Town elections offer preview of citizenship voting rules being considered nationwide Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week

Medical aid in dying, education funding, transgender issues: What to look for in the State House this week On the Trail: Shaheen’s retirement sparks a competitive NH Senate race

On the Trail: Shaheen’s retirement sparks a competitive NH Senate race